“I’m hungry,” says Onwas, squatting by his fire, blinking placidly through the smoke. The men beside him murmur in assent. It’s late at night, deep in the East African bush. Some singing, a rhythmic chant, drifts over from the women’s camp. Onwas mentions a tree he spotted during his daytime travels. The men around the fire push closer. It is in a difficult spot, Onwas explains, at the summit of one of the steep, boulder-capped hills that rise from the grassy plain. But the tree, he adds, spreading his arms wide like branches, is heavy with baboons. There are more murmurs. Embers rise to a sky infinite with stars. And then it is agreed. Everyone stands and grabs his hunting bow.

Onwas is an old man, perhaps over sixty — years are not a unit of time he uses — but thin and fit in the Hadza way. He’s maybe five feet tall. Across his arms and chest are the hieroglyphs of a lifetime in the bush: scars from hunts, scars from snakebites, scars from arrows and knives and scorpions and thorns. Scars from falling out of a baobab tree. Scars from a leopard attack. Half his teeth remain. He is wearing tire-tread sandals and tattered brown shorts. A hunting knife is strapped to his hip, in a sheath made of dik-dik hide. He’s removed his shirt, as have most of the other men, because he wants to blend into the night.

Onwas looks at me and speaks for a few moments in his native language, Hadzane. To my ear it sounds strangely bipolar — lilting and gentle for a phrase or two, then jarring and percussive, with tongue clicks and glottic pops. It’s a language not closely related to any other that still exists: to use the linguists’ term, an isolate.

I have arrived in the Hadza homeland in northern Tanzania with an interpreter, a Hadza woman named Mariamu, who married a man from a neighboring tribe and left the bush. She is Onwas’s niece. She attended school for eleven years and is one of only a handful of people in the world who can speak both English and Hadzane. She translates Onwas’s words: Do I want to come?

Merely getting this far, to a traditional Hadza encampment, is not an easy task. Years aren’t the only unit of time the Hadza do not keep close track of — they also ignore hours and days and weeks and months. The Hadza language doesn’t have words for numbers past four. Making an appointment can be a tricky matter. But I had contacted the owner of a tourist camp not far outside the Hadza territory to see if he could arrange for me to spend time with a remote Hadza group. While on a camping trip in the bush, the owner came across Onwas and asked him, in Swahili, if I might visit. The Hadza tend to be gregarious people, and Onwas readily agreed. He said I’d be the first foreigner ever to live in his camp. He promised to send his son to a particular tree at the edge of the bush to meet me when I was scheduled to arrive, in three weeks.

Sure enough, three weeks later, when my interpreter and I arrived by Land Rover in the bush, there was Onwas’s son Ngaola waiting for us. Apparently, Onwas had noted the stages of the moon, and when he felt enough time had passed, he sent his son to the tree. I asked Ngaola if he’d waited a long time for me. “No,” he said. “Only a few days.”

At first, it was clear that everyone in camp — about two dozen Hadza, ranging from infants to grandparents — felt uncomfortable with my presence. There was a lot of staring, some nervous laughs. I’d brought along a photo album, and passing it around helped mitigate the awkwardness. Onwas was interested in a picture of my cat. “How does it taste?” he asked. One photo captured everyone’s attention. It was of me participating in a New Year’s Day polar bear swim, leaping into a hole cut in a frozen lake. Hadza hunters can seem fearless; Onwas regularly sneaks up on leopards and races after giraffes. But the idea of winter weather terrified him. He ran around camp with the picture, telling everyone I was a brave man, and this helped greatly with my acceptance. A man who can leap into ice, Onwas must have figured, is certainly a man who’d have no trouble facing a wild baboon. So on the third night of my stay, he asks if I want to join the hunting trip.

—

I do. I leave my shirt on — my skin does not blend well with the night — and I follow Onwas and ten other hunters and two younger boys out of camp in a single-file line. Walking through Hadza country in the dark is challenging; thornbushes and spiked acacia trees dominate the terrain, and even during the day there is no way to avoid being jabbed and scratched and punctured. A long trek in the Hadza bush can feel like receiving a gradual full-body tattoo. The Hadza spend a significant portion of their rest time digging thorns out of one another with the tips of their knives.

At night the thorns are all but invisible, and navigation seems impossible. There are no trails and few landmarks. To walk confidently in the bush, in the dark, without a flashlight, requires the sort of familiarity one has with, say, one’s own bedroom. Except this is a thousand-square-mile bedroom, with lions and leopards and hyenas prowling in the shadows.

For Onwas such navigation is no problem. He has lived all his life in the bush. He can start a fire, twirling a stick between his palms, in less than thirty seconds. He can converse with a honeyguide bird, whistling back and forth, and be led directly to a teeming beehive. He knows everything there is to know about the bush and virtually nothing of the land beyond. One time I showed Onwas a map of the world. I spread it open on the dirt and anchored the corners with stones. A crowd gathered. Onwas stared. I pointed out the continent of Africa, then the country of Tanzania, then the region where he lived. I showed him the United States.

I asked him what he knew about America — the name of the president, the capital city. He said he knew nothing. He could not name the leader of his own country. I asked him, as politely as possible, if he knew anything about any country. He paused for a moment, evidently deep in thought, then suddenly shouted, “London!” He couldn’t say precisely what London was. He just knew it was someplace not in the bush.

—

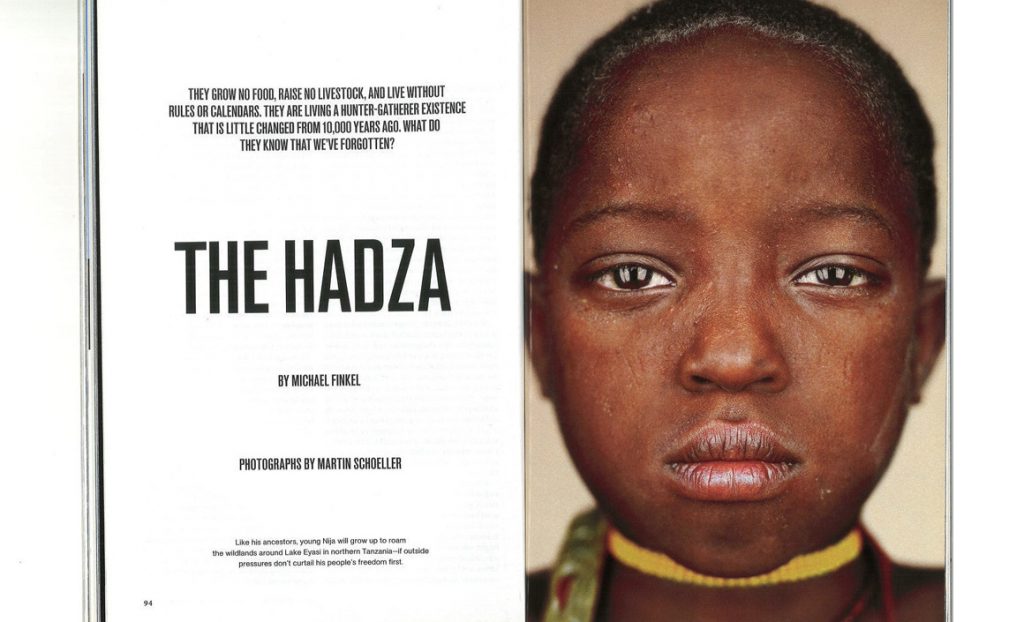

About a thousand Hadza live in their traditional homeland, a broad plain encompassing shallow, salty Lake Eyasi and sheltered by the ramparts of the Great Rift Valley. Some have moved close to villages and taken jobs as farmhands or tour guides. But approximately one-quarter of all Hadza, including those in Onwas’s camp, remain true hunter-gatherers. They have no crops, no livestock, no permanent shelters. They live just south of the area where some of the oldest fossil evidence of early humans has been found. Genetic testing indicates that they may represent one of the primary roots of the human family tree — perhaps more than 100,000 years old.

What the Hadza appear to offer — and why they are of great interest to anthropologists — is a glimpse of what life may have been like before the birth of agriculture ten thousand years ago. Anthropologists are wary of viewing contemporary hunter-gatherers as “living fossils,” says Frank Marlowe, a Florida State University professor of anthropology who has spent the past fifteen years studying the Hadza. Time has not stood still for them. But they have maintained their foraging lifestyle in spite of long exposure to surrounding agriculturalist groups, and, says Marlowe, it’s possible that their lives have changed very little over the ages.

For more than ninety-nine percent of the time since the genus Homo arose two million years ago, everyone lived as hunter-gatherers. Then, once plants and animals were domesticated, the discovery sparked a complete reorganization of the globe. Food production allowed for greater population densities, and soon farm-based societies displaced or destroyed hunter-gatherer groups. Villages were formed, then cities, then nations. And in a relatively brief period, the hunter-gatherer lifestyle was all but extinguished. Today only a handful of scattered peoples — some in the Amazon, a couple in the Arctic, a few in Papua New Guinea, and a tiny number of African groups — maintain a primarily hunter-gatherer existence. Agriculture’s sudden rise, however, came with a price. It introduced infectious-disease epidemics, social stratification, intermittent famines, and large-scale war. Jared Diamond, the UCLA professor and writer, has called the adoption of agriculture nothing less than “the worst mistake in human history” — a mistake, he suggests, from which we have never recovered.

—

The Hadza do not engage in warfare. They’ve never lived densely enough to be seriously threatened by an infectious outbreak. They have no known history of famine; rather, there is evidence of people from a farming group coming to live with them during a time of crop failure. The Hadza diet remains even today more stable and varied than that of most of the world’s citizens. They enjoy an extraordinary amount of leisure time. Anthropologists have estimated that they “work” — actively pursue food — about four hours a day. And over all these thousands of years, they’ve left hardly more than a footprint on the land.

Traditional Hadza, like Onwas and his camp mates, live almost entirely free of possessions. The things they own — a cooking pot, a water container, an ax — can be wrapped in a blanket and carried over a shoulder. Hadza women gather berries and baobab fruit and dig edible tubers. Men collect honey and hunt. Nighttime baboon stalking is a group affair, conducted only a handful of times each year; typically, hunting is a solo pursuit. They will eat almost anything they can kill, from birds to wildebeest to zebras to buffalo. They dine on warthog and bush pig and hyrax. They love baboon; Onwas told me that a Hadza man cannot marry until he has killed five baboons. The chief exception is snakes. The Hadza hate snakes.

The poison the men smear on their arrowheads, made of the boiled sap of the desert rose, is powerful enough to bring down a giraffe. But it cannot kill a full-grown elephant. If hunters come across a recently dead elephant, they will crawl inside and cut out meat and organs and fat and cook them over a fire. Sometimes, rather than drag a large animal back to camp, the entire camp will move to the carcass.

Hadza camps are loose affiliations of relatives and in-laws and friends. Each camp has a few core members — Onwas’s two sons, Giga and Ngaola, are often with him — but most others come and go as they please. The Hadza recognize no official leaders. Camps are traditionally named after a senior male (hence, Onwas’s camp), but this honor does not confer any particular power. Individual autonomy is the hallmark of the Hadza. No Hadza adult has authority over any other. None has more wealth; or, rather, they all have no wealth. There are few social obligations — no birthdays, no religious holidays, no anniversaries.

People sleep whenever they want. Some stay up much of the night and doze during the heat of the day. Dawn and dusk are the prime hunting times; otherwise, the men often hang out in camp, straightening arrow shafts, whittling bows, making bowstrings out of the ligaments of giraffes or impalas, hammering nails into arrowheads. They trade honey for the nails and for secondhand clothing and for colorful plastic and glass beads that the women fashion into necklaces. If a man receives one as a gift, it’s a good sign he has a female admirer.

There are no wedding ceremonies. A couple that sleeps at the same fire for a while may eventually refer to themselves as married. Most of the Hadza I met, men and women alike, were serial monogamists, changing spouses every few years. Onwas is an exception; he and his wife, Mille, have been with each other all their adult lives, and they have seven living children and several grandchildren. There was a bevy of children in the camp, with the resident grandmother, a tiny, cheerful lady named Nsalu, running a sort of day care while the adults were in the bush. Except for breast-feeding infants, it was hard to determine which kids belonged to which parents.

Gender roles are distinct, but for women there is none of the forced subservience knit into many other cultures. A significant number of Hadza women who marry out of the group soon return, unwilling to accept bullying treatment. Among the Hadza, women are frequently the ones who initiate a breakup — woe to the man who proves himself an incompetent hunter or treats his wife poorly. In Onwas’s camp, some of the loudest, brashest members were women. One in particular, Nduku, appointed herself my language teacher and spent a good percentage of every lesson teasing me mercilessly, often rolling around in laughter as I failed miserably at reproducing the distinct, tongue-tricky clicks.

Onwas knows of about twenty Hadza groups roaming the bush in his area, constantly swapping members, like a giant square dance. Most conflicts are resolved by the feuding parties simply separating into different camps. If a hunter brings home a kill, it is shared by everyone in his camp. This is why the camp size is usually no more than thirty people — that’s the largest number who can share a good-size game animal or two and feel decently sated.

I was there during the six-month dry season, May through October, when the Hadza sleep in the open, wrapped in a thin blanket beside a campfire — two to six people at each hearth, eight or nine fires spread in a wide semicircle fronting a brush-swept common area. The sleep groupings were various: families, single men, young women (with an older woman as minder), couples. During the rainy season, they construct little domed shelters made of interwoven twigs and long grasses; basically, upside-down bird’s nests. To build one takes no more than an hour. They move camp roughly once a month, when the berries run low or the hunting becomes tough or there’s a severe sickness or death.

No one sleeps alone in Onwas’s camp. He assigned his son Ngaola, the one who had waited a few days by the tree, to stay with me, and Ngaola recruited his friend Maduru to join us. The three of us slept in a triangle, head to toe to head around our fire, though when the mosquitoes were fierce, I retreated to my tent.

Ngaola is quiet and introspective and a really poor hunter. He’s about thirty years old and still unmarried; bedeviled, perhaps, by the five-baboon rule. It pains him that his older brother, Giga, is probably the most skilled archer in camp. Maduru is a solid outdoorsman, an especially good honey finder, but something of a Hadza misfit. When a natural snakebite remedy was passed around camp, a rare type of bark that is ground up and rubbed into the wound, Maduru was left out of the distribution. This upset him greatly, and Onwas had to spend an hour beside him, an arm slung avuncularly over his shoulder, calming him down.

—

Maduru is the one who assumes responsibility for me during the nighttime baboon quest. As we move through the bush, he snaps off eye-level acacia branches with thorns the size of toothpicks and repeatedly checks to make sure I’m keeping pace. Onwas leads us to the hill where he’d seen the tree full of baboons.

Here we stop. There are hand signals, some clipped chatter. I’m unsure of what is going on — my translator has remained back at camp. The hunt is only for men. But Maduru taps me on the shoulder and motions for me to follow. The other hunters begin fanning out around the base of the hill, and I tail Maduru as he plunges into the brush and starts to climb. The slope seems practically vertical — hands are required to haul yourself up — and the thickets are as dense as Brillo pads. Thorns slice into my hands, my face. A trickle of blood oozes into my eye. We climb. I follow Maduru closely; I do not want to become separated. I can hear, to my right and left, other Hadza hunters, also ascending.

Finally, I understand. We are climbing up, from all sides, toward the baboons. We are trying to startle them, to make them run. From the baboons’ perch atop the hill, there is no place to go but down. The Hadza have encircled the hill; therefore, the baboons will be running toward the hunters. Possibly toward Maduru and me.

Have you ever seen a baboon up close? They have teeth designed for ripping flesh. An adult male can weigh more than eighty pounds. And here we are, marching upward, purposely trying to provoke them. The Hadza are armed with bows and arrows. I have a pocketknife.

We move higher. Maduru and I break out of the undergrowth and onto the rocks. I feel as though I’ve emerged from beneath a blanket. There is a sickle of moon, a breeze. We are near the summit — the top is just over a stack of boulders, maybe twenty feet above our heads. The baboon tree is up there, barely out of eyesight.

Then I hear it — a crazed screeching sound. The baboons are aware that something is amiss. The sound is piercing, panicked. I do not speak baboon, though it isn’t difficult to interpret. Go away! Do not come closer! But Maduru clambers farther, up onto a flat rock. I follow. The baboons are surrounded, and they seem to sense it.

Abruptly, there’s a new sound. The crack of branches snapping overhead. The baboons are descending, shrieking. Maduru freezes, drops to one knee, slides an arrow into position, pulls back the bowstring. He is ready. I’m hiding behind him. I hope, I fervently hope, that no baboons run at us. I reach into my pocket, pull out my knife, unfold it. The blade is maybe two inches long. It feels ridiculous, but that is what I do.

The screeching intensifies. And then, directly over us, in stark silhouette against the backdrop of stars, is a baboon. Scrambling. Moving along the rock’s lip. Maduru stands, takes aim, tracking the baboon from left to right, the arrow slotted, the bowstring at maximum stretch. Every muscle in my body tenses. My head pulses with panic. I grip my knife.

—

If you ask Onwas how long the Hadza have been hunting baboons, using this same style, among these same hills, he will wrinkle his forehead and affix you with a funny look and say that the Hadza have always hunted this way. His father, Duwau, hunted this way. His father’s father, Washema, hunted this way. His father’s father’s father, Buluku, hunted this way. And so on, until the beginning of time.

The chief reason the Hadza have been able to maintain their lifestyle so long is that their homeland has never been an inviting place. The soil is briny; fresh water is scarce; the bugs can be intolerable. For tens of thousands of years, it seems, no one else wanted to live here. So the Hadza were left alone. Recently, however, escalating population pressures have brought a flood of people into Hadza lands. The fact that the Hadza are such gentle stewards of the land has, in a way, hurt them — the region has generally been viewed by outsiders as empty and unused, a place sorely in need of development. The Hadza, who by nature are not a combative people, have almost always moved away rather than fight. But now there is nowhere to retreat.

There are currently cattle herders in the Hadza bush, and goat herders, and onion farmers, and corn growers, and sport hunters, and game poachers. Water holes are fouled by cow excrement. Vegetation is trampled beneath cattle’s hooves. Brush is cleared to make way for crops; scarce water is used to irrigate them. Game animals have migrated to national parks, where the Hadza can’t follow. Berry groves and trees that attract bees have been destroyed. Over the past century, the Hadza have lost exclusive possession of as much as ninety percent of their homeland.

None of the other ethnic groups living in the area — the Datoga, the Iraqw, the Isanzu, the Sukuma, the Iramba — are hunter-gatherers. They live in mud huts, often surrounded by livestock enclosures. Many of them look down on the Hadza and view them with a mix of pity and disgust: the untouchables of Tanzania. I once watched as a Datoga tribesman prevented several Hadza women from approaching a communal water hole until his cows had finished drinking.

Dirt roads are now carved into the edges of the Hadza bush. A paved road is within a four-day walk. From many high points there is decent cell phone reception. Most Hadza, including Onwas, have learned to speak some Swahili, in order to communicate with other groups. I was asked by a few of the younger Hadza hunters if I could give them a gun, to make it easier to harvest game. Onwas himself, though he’s scarcely ventured beyond the periphery of the bush, senses that profound changes are coming. This does not appear to bother him. Onwas, as he repeatedly told me, doesn’t worry about the future. He insists he doesn’t worry about anything. No Hadza I met, in fact, seemed prone to worry. It was a mind-set that astounded me, for the Hadza, to my way of thinking, have very legitimate worries. Will I eat tomorrow? Will something eat me tomorrow? Yet they live a remarkably present-tense existence.

This may be one reason farming has never appealed to the Hadza — growing crops requires planning; seeds are sown now for plants that won’t be edible for months. Domestic animals must be fed and protected long before they’re ready to butcher. To a Hadza, this makes no sense. Why grow food or rear animals when it’s being done for you, naturally, in the bush? When they want berries, they walk to a berry shrub. When they desire baobab fruit, they visit a baobab tree. Honey waits for them in wild hives. And they keep their meat in the biggest storehouse in the world — their land. All that’s required is a bit of stalking and a well-shot arrow.

There are other people, however, who do ponder the Hadza’s future. Officials in the Tanzanian government, for starters. Tanzania is a future-oriented nation, anxious to merge into the slipstream of the global economy. Baboon-hunting bushmen is not an image many of the country’s leaders wish to project. One minister has referred to the Hadza as backward. Tanzania’s president, Jakaya Kikwete, has said that the Hadza “have to be transformed.” The government wants them schooled and housed and set to work at proper jobs.

Even the one Hadza who has become the group’s de facto spokesperson, a man named Richard Baalow, generally agrees with the government’s aims. Baalow, who adopted a non-Hadza first name, was one of the first Hadza to attend school. In the 1960s his family lived in government-built housing — an attempt at settling the Hadza that soon failed. Baalow, who says he’s fifty-three years old, speaks excellent English. He wants the Hadza to become politically active, to fight for legal protection of their land, and to seek jobs as hunting guides or park rangers. He encourages Hadza children to attend the regional primary school that provides room and board to Hadza students during the academic year, then escorts them back to the bush when school is out.

The school-age kids I spoke with in Onwas’s group all said they had no interest in sitting in a classroom. If they went to school, many told me, they’d never master the skills needed for survival. They’d be outcasts among their own people. And if they tried their luck in the modern world — what then? The women, perhaps, could become maids; the men, menial laborers. It’s far better, they said, to be free and fed in the bush than destitute and hungry in the city.

More Hadza have moved to the ancestral Hadza area of Mangola, at the edge of the bush, where, in exchange for money, they demonstrate their hunting skills to tourists. These Hadza have proved that their culture is of significant interest to outsiders and a potential source of income. Yet among the Hadza of Mangola there has also been a surge in alcoholism, an outbreak of tuberculosis, and a distressing rise in domestic violence, including at least one report of a Hadza man who beat his wife to death.

Though the youngsters in Onwas’s group show little interest in the outside world, the world is coming to them. After two million years, the age of the hunter-gatherer is over. The Hadza may hold on to their language; they may demonstrate their abilities to tourists. But it’s only a matter of time before there are no more traditional Hadza scrambling in the hills with their bows and arrows, stalking baboons.

—

Up on the hill Onwas has led us to, clutching my knife, I crouch behind Maduru as the baboon moves along a fin of rock. And then, abruptly, the baboon stops. He swivels his head. He is so close we could reach out to each other and make contact. I stare into his eyes, too frightened to even blink. This lasts maybe a second. Maduru doesn’t shoot, possibly because the animal is too close and could attack us if wounded –it’s often the poison, not the arrow, that kills. An instant later the baboon leaps away into the bushes.

There is silence for a couple of heartbeats. Then I hear frantic yelping and crashing. It’s coming from the far side of the rock, and I can’t tell if it is human or baboon. It’s both. Maduru darts off, and I race after him. We thrash through bushes, half-tumbling, half-running, until we reach a clearing amid a copse of acacias.

And there it is: the baboon. On his back, mouth open, limbs splayed; an adult male. Shot by Giga. A nudge with a toe confirms it — dead. Maduru whistles and shouts, and soon the other hunters arrive. No other baboon has been killed; the rest of the troop managed to evade the hunters. Onwas kneels and pulls the arrow out of the baboon’s shoulder and hands it back to Giga. The men stand around the baboon in a circle, examining the kill. There is no ceremony. The Hadza are not big on ritual. There is not much room in their lives, it seems, for mysticism, for spirits, for pondering the unknown. There is no specific belief in an afterlife — every Hadza I spoke with said he had no idea what might happen after he died. There are no Hadza priests or shamans or medicine men. Missionaries have produced few converts. I once asked Onwas to tell me about God, and he said that God was blindingly bright, extremely powerful, and essential for all life. God, he told me, was the sun.

The most important Hadza ritual is the epeme dance, which takes place on moonless nights. Men and women divide into separate groups. The women sing while the men, one at a time, don a feathered headdress and tie bells around their ankles and strut about, stomping their right foot in time with the singing. Supposedly, on epeme nights, ancestors emerge from the bush and join the dancing. One night when I watched the epeme, I spotted a teenage boy, Mataiyo, sneak into the bush with a young woman. Other men fell asleep after their turn dancing. Like almost every aspect of Hadza life, the ceremony was informal, with a strictly individual choice of how deeply to participate.

With the Hadza god not due to rise for several hours, Giga grabs the baboon by a rear paw and drags the animal through the bush back to camp. The baboon is deposited by Onwas’s fire, while Giga sits quietly aside with the other men. It is Hadza custom that the hunter who’s made the kill does not show off. The blood on his arrow shaft is sign enough; word will get around. There is a good deal of luck in hunting, and even the best archers will occasionally face a long dry spell. This is why the Hadza share their meat communally.

Onwas’s wife, Mille, is the first to wake. She’s wearing her only set of clothes, a sleeveless T-shirt and a flower-patterned cloth wrapped about her like a toga. She sees the baboon, and with the merest sign of pleasure, a brief nod of her chin, she stokes the fire. It’s time to cook. The rest of camp is soon awake — everyone is hungry — and Ngaola skins the baboon and stakes out the pelt with sharpened twigs. The skin will be dry in a few days and will make a fine sleeping mat. A couple of men butcher the animal, and cuts of meat are distributed. Onwas, as camp elder, is handed the greatest delicacy: the head.

The Hadza cooking style is simple — the meat is placed directly on the fire. No grill, no pan. Hadza mealtime is not an occasion for politeness. Personal space is generally not recognized; no matter how packed it is around a fire, there’s always room for one more, even if you end up on someone’s lap. Once a cut of meat has finished cooking, anyone can grab a bite.

And I mean grab. When the meat is ready, knives are unsheathed and the frenzy begins. There is grasping and slicing and chewing and pulling. The idea is to tug at a hunk of meat with your teeth, then use your knife to slice away your share. Elbowing and shoving is standard behavior. Bones are smashed with rocks and the marrow sucked out. Grease is rubbed on the skin as a sort of moisturizer. No one speaks a word, but the smacking of lips and gnashing of teeth is almost comically loud.

I’m ravenous, so I dive into the scrum and snatch up some meat. Baboon steak, I have to say, isn’t terrible — a touch gamey, but it’s been a few days since I’ve eaten protein, and I can feel my body perking up with every bite. Pure fat, rather than meat, is what the Hadza crave, though most coveted are the baboon’s paw pads. I snag a bit of one and pop it in my mouth, but it’s like trying to swallow a pencil eraser. When I spit the gob of paw pad out, a young boy instantly picks it up and swallows it.

Onwas, with the baboon’s head, is comfortably above the fray. He sits cross-legged at his fire and eats the cheeks, the eyeballs, the neck meat, and the forehead skin, using the soles of his sandals as a cutting board. He gnaws the skull clean to the bone, then plunges it into the fire and calls me and the hunters over for a smoke.

It is impossible to overstate just how much Onwas — and most Hadza — love to smoke. The four possessions every Hadza man owns are a bow, some arrows, a knife, and a pipe, made from a hollowed-out, soft stone found only in a secret spot on their land. The smoking material, tobacco or cannabis, is acquired from a neighboring group, usually the Datoga, in exchange for honey. Onwas has a small amount of tobacco, which is tied into a ball inside his shirttail. He retrieves it, stuffs it all into his pipe, and then, holding the pipe vertically, plucks an ember from the fire — Onwas, like every Hadza, seems to have heat-impervious fingertips — and places it atop his pipe. Pulsing his cheeks in and out like a bellows, he inhales the greatest quantity of smoke he possibly can. He passes the pipe to Giga.

Then the fun begins. Onwas starts to cough, slowly at first, then rapidly, then uncontrollably with tears bursting from his eyes, then with palms pushing against his head, and then, finally, rolling onto his back, spitting and gasping for air. In the meantime, Giga has begun a similar hacking session and has passed the pipe to Maduru, who then passes the pipe to me. Soon, all of us, the whole circle of men, are hacking and crying and rolling on our backs. The smoke session ends when the last man sits up, grinning, and brushes the dirt from his hair.

With the baboon skull still in the fire, Onwas rises to his feet and claps his hands and begins to speak. After a minute, I realize it’s a giraffe-hunting story — Onwas’s favorite kind. I know this even though Mariamu, my translator, is not next to me. I know because Onwas, like many Hadza, is a story performer. There are no televisions or board games or books in Onwas’s camp. But there is entertainment. The women sing songs. And the men tell campfire stories, the Kabuki of the bush.

Onwas elongates his neck and moves around on all fours when he’s playing the part of the giraffe. He jumps and ducks and pantomimes shooting a bow when he’s illustrating his own role. Arrows whoosh. Beasts roar. Children run to the fire and stand around, listening intently. Onwas is demonstrating how he hunts; this is their schooling. The story ends with a dead giraffe — and as a finale, a call and response.

“Am I a man?” asks Onwas, holding out his hands.

“Yes!” shouts the group. “You are a man.”

“Am I a man?” asks Onwas again, louder.

“Yes!” shouts the group, their voices also louder. “You are a man!”

Onwas then reaches into the fire and pulls out the skull. He hacks it open, like a coconut, exposing the brains, which have been boiling for a good hour inside the skull. They look like ramen noodles, yellowish white, lightly steaming. He holds the skull out, and the men, including myself, surge forward and stick our fingers inside the skull and scoop up a handful of brains and slurp them down. With this, the night, at last, comes to an end.

—

The baboon hunt, it seems, was something of an initiation for me. The next day, Nyudu, one of the camp’s most consistently successful hunters, hacks down a thick branch from a mutateko tree, then carefully carves a bow for me, long and gracefully curved. Several other men make me arrows. Onwas presents me with a pipe. An older hunter named Nkulu handles my shooting lessons. I begin to carry my bow and arrows and pipe with me wherever I go (along with my water-purification kit, my sunscreen, my bug spray, and my eyeglass-cleaning cloth).

I am also invited to bathe with the men. We walk to a shallow, muddy hole — more of a large puddle, with lumps of cow manure bobbing about — and remove our clothes. Handfuls of mud are rubbed against the skin as an exfoliant, and we splash ourselves clean. Hadza men are not circumcised. Until recently, according to researchers, most Hadza women were circumcised, though now, due in part to governmental intervention, it is seldom done.

The men tell me that they prefer their women not to bathe — the longer they go between baths, they say, the more attractive they are. Nduku, my Hadza language teacher, said she sometimes waits months between baths, though she can’t understand why her husband wants her that way. I learn, as well, why I do not hear any Hadza making love. They eat loudly, and they smoke loudly, but it turns out that they are especially quiet when it comes to sex. They rarely even kiss in front of anyone else. Onwas said he’d never heard of a homosexual Hadza.

I also discover, by listening to Mille and Onwas, that bickering with one’s spouse is probably a universal human trait. “Isn’t it your turn to fetch water?” “Why are you napping instead of hunting?” “Can you explain why the last animal brought to camp was skinned so poorly?” It occurs to me that these same arguments, in this same valley, have been taking place for thousands of years.

There are things I envy about the Hadza — mostly, how free they appear to be. Free from possessions. Free of most social duties. Free from religious strictures. Free of many family responsibilities. Free from schedules, jobs, bosses, bills, traffic, taxes, laws, news, and money. Free from worry. Free to burp and fart without apology, to grab food and smoke and run shirtless through the thorns.

But I could never live like the Hadza. Their entire life, it appears to me, is one insanely committed camping trip. It’s incredibly risky. Medical help is far away. One bad fall from a tree, one bite from a black mamba snake, one lunge from a lion, and you’re dead. Women give birth in the bush, squatting. About a fifth of all babies die within their first year, and nearly half of all children do not make it to age fifteen. They have to cope with extreme heat and frequent thirst and swarming tsetse flies and malaria-laced mosquitoes.

The days I spent in Onwas’s camp altered my perception of the world. They instilled in me something I call the “Hadza effect” — they made me feel calmer, more attuned to the moment, more self-sufficient, a little braver, and in less of a constant rush. I don’t care if this sounds maudlin: My time with the Hadza made me happier. It made me wish there was some way to prolong the reign of the hunter-gatherers, though I know it’s almost certainly too late.

It was my body, more than anything, that let me know it was time to leave the bush. I was bitten and bruised and sunburned and stomachachy and exhausted. So, after two weeks, I told everyone in camp I had to go.

There was little reaction. The Hadza are not sentimental like that. They don’t do extended goodbyes. Even when one of their own dies, there is not a lot of fuss. They dig a hole and place the body inside. A generation ago, they didn’t even do that — they simply left a body out on the ground to be eaten by hyenas. There is still no Hadza grave marker. There is no funeral. There’s no service at all, of any sort. This could be a person they had lived with their entire life. Yet they just toss a few dry twigs on top of the grave. And they walk away.

— end —