The Khan dreams of a car. Never mind that there isn’t a road. His father, the previous Khan, spent his life lobbying for a road. The new Khan does the same. A road, he argues, would permit doctors, and their medicines, to easily reach them. Then maybe all the dying would stop. Teachers too could get to them. Also traders. There could be vegetables. And then his people — the Kyrgyz nomads of remote Afghanistan — might have a legitimate chance to thrive. A road is the Khan’s work. A car is his dream.

“What kind of car?” I ask.

“Whatever car you want to give me,” he says. The ends of his mustache curl around a smile.

But for now, with no car and no road, the reality is a yak. The Khan is holding one by a rope strung through its nose. Other yaks are standing by. It’s moving day; everything the Khan owns needs to be tied to the back of a yak. This includes a dozen teapots, a cast-iron stove, a car battery, two solar panels, a yurt, and forty-three blankets. His younger brother and a few others are helping. The yaks buck and kick and snort; loading them is as much wrestling as packing.

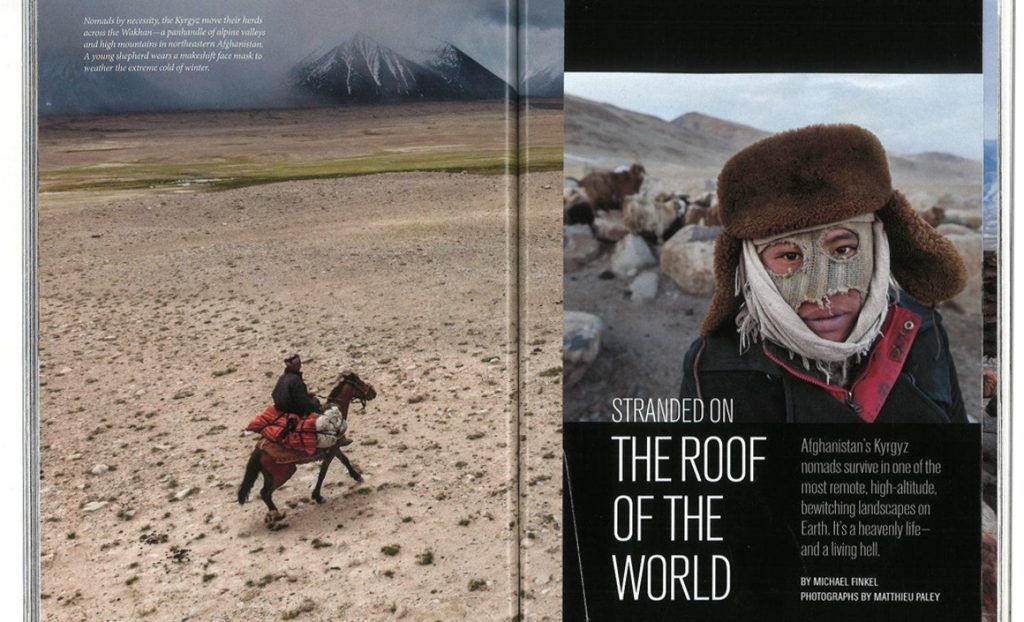

Moving is what nomads do. For the Kyrgyz of Afghanistan, it’s from two to four times a year, depending on the weather and the availability of grass for the animals. They call their homeland Bam-e Dunya, which means “roof of the world.” This might sound poetic and beautiful — it is undeniably beautiful — but it’s also an environment at the very cusp of human survivability. Their land consists of two long, glacier-carved valleys, called pamirs, stashed deep within the great mountains of Central Asia. Much of it is above 14,000 feet. The wind is furious; crops are impossible to grow. The temperature can drop below freezing 340 days a year. Many Kyrgyz have never seen a tree.

The valleys are located in a strange, pincer-shaped appendage of land jutting from the northeast corner of Afghanistan. This strip, often referred to as the Wakhan corridor, was a result of the nineteenth century’s so-called Great Game, when the British and Russian Empires fought for influence in Central Asia. The two powers created it, through a series of treaties between 1873 and 1895, as a buffer zone — a sort of geographical shock absorber — preventing tsarist Russia from touching British India. In previous centuries the area was part of the Silk Road connecting China and points west, the route of armies and explorers and missionaries. Marco Polo passed through in the late 1200s.

But communist revolutions — Russia in 1917, China in 1949 — eventually sealed the borders. What was once a conduit became a cul-de-sac. Now, in the postcolonial age, the corridor is bordered by Tajikistan to the north, Pakistan to the south, and China to the east. Mainland Afghanistan, to the west, can seem so far away — the corridor is about 200 miles long — that some Kyrgyz refer to it as a foreign country. They feel locked in a distant outpost, encaged by a spiked fence of snowy peaks, lost in the swirl of history and politics and conflict.

To reach the nearest existing road — the road the Khan wants extended into Kyrgyz territory — requires at least a three-day journey through the mountains, on a trail where a fall could be deadly. The closest significant town, one with shops and a basic hospital, is an additional day’s travel. This intense isolation is the reason the Kyrgyz suffer from a catastrophic death rate. There’s no doctor, no health clinic, few medicines. In the harsh environment, even a minor ailment — a sniffle, a headache — can swiftly turn virulent. The death rate for children among the Afghan Kyrgyz may be the highest in the world. Less than half live to their fifth birthday. It is not unusual for parents to lose five children, or six, or seven. Women die at an alarming rate while giving birth.

I met one couple, Halcha Khan and Abdul Metalib, who had eleven children. “Every year,” said Abdul, “one would die.” They died as infants, as toddlers, as little kids. Many likely died from easily treatable diseases. Each was wrapped in a white shroud and buried in a shallow grave. “That cut me into pieces,” said Abdul. To numb the pain, Halcha and Abdul turned to opium. The drug’s easy availability has created an epidemic of addiction among the Kyrgyz. Only one of their children, a son, survived to age five. Then he too passed away.

—

The Khan knows about the outside world. He has twice traveled beyond the Wakhan region, and he exchanges news with merchants who venture into Kyrgyz land, trading his animals for goods like cloth, jewelry, opium, sunglasses, saddles, carpets, and lately, cell phones — not for calls (there’s no reception) but for playing music and taking pictures.

The Khan realizes that the rest of the planet, day by day, is leaving his people behind. The Kyrgyz nomads, with a total population of about 1,100, have only just begun a rudimentary educational system. The Khan himself has never learned to read or write. He knows that almost everyone else has access to medical help, that the world is connected by cars and computers. He knows that children aren’t supposed to die like this.

It is a lot for a young leader to bear. And the Khan is young. He’s only thirty-three, and looks it — even his mustache, with its expressive little Fu Manchu tips, can’t mask his boyish appearance. He’s on the short side as well, no more than five feet seven, and moves with a nervous, jackrabbity energy. He has light brown eyes and ruddy, wind-chapped skin and is partial to wearing a fur-lined cap with the earflaps tied overhead. He dresses, like most Kyrgyz men, in an all-black outfit, jacket to pants to shoes. He’s not above telling the occasional dirty joke.

His name is Hajji Roshan Khan. He and his wife, Toiluk, have four daughters. The “Hajji” part of his name is an honorific, meaning he’s been to Mecca. The Kyrgyz are Sunni Muslims, and in 2008 his father, Abdul Rashid Khan, took him — him alone out of fourteen children — to Saudi Arabia. That was the first time he’d left the Wakhan. The other time was last spring, when he traveled to Kabul and met with ministers in the Afghan government, as well as President Hamid Karzai, pleading for funding to build a medical clinic and a couple of schools and, of course, the road.

Though his father was the Khan, the position of tribal leader is not hereditary. It must be agreed upon by the elders of the community. When Abdul Rashid Khan died in 2009, it was clear from his choice of traveling companion to Mecca whom he wished to succeed him. That summer, Er Ali Bai, one of the more respected Kyrgyz, invited the leading elders to his camp. A camp is the chief division of Kyrgyz life — three to ten families who migrate together and share the herding of yaks and fat-tailed sheep and long-haired goats.

The Kyrgyz are not poor. Though paper money is almost nonexistent, many camps’ herds contain hundreds of valuable animals, including the horses and donkeys used for transportation. The basic unit of Kyrgyz currency is a sheep. A cell phone costs one sheep. A yak costs about ten sheep. A high-quality horse is fifty. The going rate for a bride is one hundred. The wealthiest families own the ultimate Kyrgyz status symbol — a camel, the two-humped kind, called a Bactrian, that appears perpetually foul tempered.

Er Ali Bai has six camels. He’s fifty-eight years old and walks with a pronounced limp, leaning on a metal hiking pole that was given to him by a visitor. When the mood strikes, he’s prone to whack somebody playfully — yet painfully — with his pole. He loves to chat on his walkie-talkie. These two-way radios, recently introduced by itinerant traders, have allowed news to be passed from camp to camp, though the resulting information is often as accurate as in the party game telephone. Er Ali Bai is the owner of the only chicken in Kyrgyz country. The chicken, a hen, has one leg. The other was lost to frostbite.

About forty men arrived at Er Ali Bai’s camp to anoint the new Khan. They sat outside on blankets, in a large circle. Sheep and goats were slaughtered, the traditional way to begin any Kyrgyz occasion. The hunk of fat around a sheep’s tail, boiled until gelatinous and pale yellow, is a great delicacy. They met for more than eight hours. In the end everybody agreed that Hajji Roshan Khan would be the new leader.

They agreed, but this doesn’t mean the Khan is well liked. In fact, many people have deep misgivings about him. This is not surprising. The Kyrgyz are notoriously fractious and independent minded. They don’t often rally around a leader, says Ted Callahan, an anthropological researcher who lived with the Kyrgyz for more than a year. A Kyrgyz joke goes that if you put three people in a yurt and come back an hour later, you’ll find five Khans.

Some say the new Khan is too young. Or too inexperienced. They say he’s an opium smoker. (He insists he’s quit.) They say he is not sangeen, which means “like a rock,” representing the strength and toughness the Kyrgyz look for in a leader. One faction argues that a rival who lives on the other end of the valley should have become Khan. Others insist there is no need for a Khan anymore; the era of the Khans is finished.

The new Khan’s biggest supporter, though, is Er Ali Bai. Some critics complain that an aksakal — a “white beard” — should have been picked. “Yes,” Er Ali Bai replies. “There are people with long beards. Goats also have long beards. Should we have selected a goat?” There’s no need for concern, he adds. “He will become a great Khan.”

Still, the young Khan worries. He’s striving to convince his people that he is the right person for this job. And he is working to resolve the tremendous problems the Kyrgyz face as they fight to survive in one of Earth’s most unforgiving environments.

—

On moving day the Khan must focus on making sure the loaded yaks arrive at his summer camp. Though it’s late June, snow falls, swirling beneath cottage cheese clouds. But the Khan can’t wait. The grass at his winter camp requires every day of the brief growing season to renew.

The Khan and his family live in a gloomy, thick-walled mud hut in winter, and in a yurt the rest of the time. Each Kyrgyz camp follows a relatively simple migration pattern, living on the warmer, south-facing side of the valley in winter, then trekking the five or so miles to the other side in summer. I catch a ride on one of the Khan’s tamer yaks and join the procession.

The horizon, everywhere you look, is halted by towering chiseled peaks. Here, on the roof of the world, several of Asia’s highest ranges meet — the Hindu Kush, the Karakoram, the Kunlun — a spot so tangled with mountains it’s known as the Pamir Knot. The Wakhan corridor is also the birthplace of rivers flowing both east and west, including the Amu Darya, or “Mother River,” one of the main waterways of Central Asia.

We reach the banks of the Aksu River. This time of year, with snowmelt accelerating, it’s deep and rapid. The Khan’s loaded yaks plunge in. Two of them lose their footing and begin drifting downstream, carried by the current, noses held above water, eyes wild, the stacks of supplies on their backs getting soaked.

The Khan’s brother-in-law, Darya Bai, charges into the water on his horse. Gripping the reins in one hand, leaning sideways in his saddle, he grabs a yak’s neck and tries to haul it across. For a moment it seems that the yaks, the supplies, and the brother-in-law might all be swept downriver. But they’re carried into an oxbow where the water flattens, and the yaks, followed by Darya Bai, soon emerge on the far bank, dripping and shaking.

Then the Khan crosses on his horse with his six-year-old daughter, Rabia, her hands clamped around his waist, feet raised to avoid getting wet. His three-year-old, Arizo, rides behind his wife, while his other children, seven-year-old Kumush Ai (“Silver Moon”) and four-year-old Jolshek, share a horse with their uncle. They reach a grassy area at the mouth of a narrow, glacier-packed side canyon. Goats stare from atop a pointy boulder. The wind — the brutal, unrelenting bad-e Wakhan — picks up. Snowflakes hurtle sideways, stinging faces. Loads are dumped from the yaks into a large pile.

The Khan’s wife and children huddle while the men begin building the yurt, listening to Kyrgyz music on a cell phone — a chanty tune featuring a three-stringed lute called a komuz. Constructing a yurt is a jigsaw puzzle feat requiring several hours. When finished, a yurt from the outside seems unimpressive, a sort of lumpy boiled potato, the whole thing covered in dirty white felt that the Kyrgyz make themselves.

The Kyrgyz are not the most gregarious people. They don’t laugh much. They own no books, no playing cards, no board games. Their one dance is unbelievably lame, little more than a gentle waving of a handkerchief. With a single exception — a young boy who filled a notebook with marvelous penciled portraits — I met no one who seemed interested in fine art or drawing. A wedding I attended was shockingly joyless, with the exception of a game of buzkashi, a fast and violent sport played on horseback with the headless carcass of a goat as the ball.

Kyrgyz manners could be considered gruff. It’s acceptable to walk away in the middle of a conversation. More than once, without asking, a man thrust his hand into my pocket to see what I kept in there. Or snatched my glasses off my nose to inspect them. The Kyrgyz eat meat by slicing off hunks and stashing the leftovers in a pocket. There’s not much singing.

Perhaps this is understandable. This is a place, as the Khan says, where “you get old fast.” Maybe, when you are always cold, when you watch a half dozen of your children die, some emotion is sandpapered away. Maybe this land is too windy, too remote, too hard. If it doesn’t kill you, it damages you; it robs you of a certain channel of joy.

—

Until you step into a Kyrgyz yurt. Move aside the heavy felt door. And suddenly everything changes. The outside world disappears, and you’ve walked into a Kyrgyz wonderland. The blankets and carpets and wall hangings and ceiling coverings are all decorated with ornate designs — paisley, flowered, spangled, psychedelic, kaleidoscopic. This is where the family eats and sleeps and escapes, in this ecstatic explosion of color.

In the center of the yurt is either an open fire or an iron stove. There’s no wood in Kyrgyz country. Instead they burn yak dung, which actually emits a sweet odor. Always, there is a teapot on the boil. Usually several. Tea is the staple of the Kyrgyz; they drink it with yak milk and salt, and they drink it constantly. “I drink 120 cups a day,” Er Ali Bai told me. He probably wasn’t exaggerating much.

The Kyrgyz also eat yak-milk yogurt, fizzy and thick, and a hard cheese called kurut, which you soften in your mouth for several minutes before chewing. Also unleavened rounds of bread the size of pizzas. Meat is reserved for special gatherings. The closest to a vegetable is a tiny wild onion, no bigger than a pea.

There is one thing more expressive than a Kyrgyz yurt. And that is a Kyrgyz woman. Men dress like they’re perpetually on their way to a funeral. Women are Kyrgyz works of art. Atop their heads are tall, cylindrical caps draped with giant head scarves — red for unmarried women, white for married — that flow behind them like superheroes’ capes.

They wear long, bright-red dresses, usually with red vests over them. Attached to this vest is an amazing mosaic of bling. Plastic shirt buttons are sewn around the collar by the dozens. There are sun-shaped brass brooches and leather pouches containing verses from the Koran. I spotted coins, keys, seashells, perfume bottles, and eagle claws. One woman had seven nail clippers pinned to her chest. Every movement by a Kyrgyz woman produces a jangling, wind-chimey tone. Their hair is styled in two or more long braids affixed with silver ornaments. They wear multiple necklaces and at least one ring on every finger except the middle ones, even the thumbs. (Calling attention to the middle finger is considered rude.) Bracelets galore. Dangly earrings. One watch is rarely enough — two or three are better. I counted as many as six.

The women perform endless chores — milking the yaks twice a day along with sewing and cooking and cleaning and babysitting. They rarely speak when men are around. I tried, politely, for half an hour to get one woman to explain why she was wearing three watches. Finally, she answered. “It’s nice,” she said. I did not exchange a word with the Khan’s wife, though I lived in their camp for a week.

The majority of women I met had never been more than a few miles from where they were born — their biggest journey was traveling to their husbands’ camps after marriage. “We are not that sort of stupid people who let women go anywhere they want,” explained the Khan. All Kyrgyz marriages are arranged, usually when a woman is in her teens. Both the Khan and his wife were fifteen when they wed.

One of the few women who chatted with me was a free-spirited widow named Bas Bibi. She guessed she was seventy years old. She’d had five sons and two daughters. They all died. “Men never milk animals,” she said. “Or wash clothes. Or cook meals. If women were not here, nobody could live a single day!”

—

Throughout their history, the Kyrgyz have always rejected the idea of being controlled by a government or serving as vassals to a king. “We are untamed humans,” one Kyrgyz man proudly informed me. Their origins are murky. The Kyrgyz are first mentioned in a Chinese document from the second century A.D. and are thought to have come from the Altay Mountains of what is now Siberia and Mongolia. The name Kyrgyz, according to anthropologist Nazif Shahrani, is possibly a compound of kyrk, meaning “forty,” and kyz, meaning “girl” — an etymology the Kyrgyz take to signify “descendants of forty maidens.”

Never a large tribe, the Afghan Kyrgyz roamed Central Asia for centuries — they were infamous for raiding Silk Road caravans — and by the 1700s had begun using the valleys where they now live as summertime grazing grounds. They’d leave to warmer areas when winter descended, avoiding the long, cruel season they must now endure. But then came the great empires, and their Great Game, followed by the spread of communism. By 1950 all the borders were shut and, says Ted Callahan, the Kyrgyz “by default became Afghan citizens,” trapped year-round in the Wakhan corridor. In 1978 a military coup upended Kabul, and there was the looming threat of a Soviet invasion. The Kyrgyz feared that Afghanistan too would become communist. Nearly all the Kyrgyz, some 1,300 people, elected to follow the Khan at the time — Rahman Kul — and escape across the Hindu Kush into Pakistan.

Disease killed a hundred during their first summer as refugees. Though Rahman Kul urged his people to remain in Pakistan — the Soviet soldiers in Afghanistan, he warned, would ban their religion and crush their freedoms — many Kyrgyz were disillusioned with his leadership. They missed their life on the roof of the world.

Soon there was a split. Abdul Rashid Khan, the current Khan’s father, led about three hundred Kyrgyz back into Afghanistan, including Er Ali Bai. This is when Abdul Rashid was designated as Khan. The Soviet troops, when they arrived, treated the Kyrgyz kindly, and over the past three decades, the population has grown to the current level of more than a thousand, even with the high death rate.

Those who remained in Pakistan with Rahman Kul eventually resettled in eastern Turkey, where they now live in a village of cookie-cutter row houses, with electricity and cable TV and paved roads and cars. They were assigned Turkish last names. They like their video games, their flush toilets. They have been tamed.

—

During his recent trip to Kabul, the Khan’s appendix swelled. He went to a hospital and had it surgically removed. Not a big deal. But it rattled him deeply. “If that had happened here,” he says, “I would have died. Lots of people die here because of that.”

Sometimes, among the Kyrgyz of Afghanistan — often at night, sipping tea in the warmth of a yurt — the question is asked: Would they be better off someplace else? Though the Kyrgyz valleys are free from the fighting that afflicts the rest of Afghanistan, living here can feel like a constant roll of the dice. The idea of leaving again, this time for good, seems always in the back of their minds. Some mention relocating to the former Soviet republic of Kyrgyzstan, where the same language is spoken and they have ethnic ties. But it is unclear whether this idea is really an option.

Even the young Khan is not immune to such thoughts. He admits, in moments of candor, that he’s imagined moving with his family, settling in a town somewhere in mainland Afghanistan. Living a more normal life. Perhaps, the Khan thinks, there comes a time to give up on your homeland.

On the Khan’s second day at his summer camp, important news arrives. Two government-employed engineers from Kabul have arrived at the end of the present road to survey routes that would extend the road through the mountains into Kyrgyz territory. The Khan must greet them, a trip that will require three days of dawn-to-dark horse riding.

From a metal trunk in his yurt, the Khan’s wife pulls out his finest clothes — a wool pin-striped suit, tall leather riding boots, a black-and-white scarf. His excitement is palpable. Maybe his people’s fortunes are about to change. “Everybody will be happy,” he says. His wife hands him a dark-blue bottle of cologne and a small brass container of naswar, the potent Afghan chewing tobacco. He climbs on his horse. There’s “a one-hundred percent chance,” he says, that the road will be built. He snaps his crop on the horse’s flank.

I watch him gallop down the valley. His confidence seems at odds with reality. In a poverty-stricken country with widespread disorder, constructing a road that would cost millions of dollars — possibly hundreds of millions — to help a thousand or so people makes little sense. “Nobody is building a road,” agrees Er Ali Bai. In the time of the Khan’s father, Er Ali Bai recalls, engineers also came by, also said they were surveying for a road. Nothing ever happened.

A road, Er Ali Bai points out, would bring its own problems. Yes, it would provide easy access for doctors and teachers. But also for tourists. And armies. The outside world would stream in — and that, Er Ali Bai says, might cause the younger generation to crave a less challenging life. To want to leave even more. “There are people who think riding in cars will make them happy,” says Er Ali Bai. “But this place is very beautiful. We live with love and family. This is the most peaceful place in the world.”

The views here are sweeping, and for a long time I see the Khan riding away, his horse kicking up reddish brown dust. It’s a gorgeous day, warm and as close to windless as it gets. I envision the Khan at the wheel of a car, windows down, hair tousled, driving past the mountain spires gleaming white in the sun. But I also understand that if the Khan is able to do this, if his work is rewarded, the road built, his dream fulfilled, then the time of the traditional Kyrgyz nomad — the tribe of rugged and proud people who have survived for almost 2,000 years — will have come to an end.

— end —