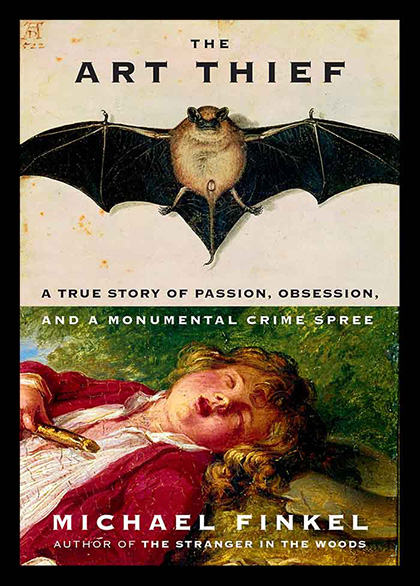

The Art Thief, like its title character, has confidence, élan, and a great sense of timing ... what makes Finkel’s book so much fun is that, without exception, [Breitwieser’s] strategies are insane.

Fascinating… has the pacing and atmosphere of a good suspense tale.

A fascinating read. Finkel will have art history and true crime lovers obsessively turning the pages of this suspenseful, smartly written work until its shocking conclusion.

Masterful ... a riveting ride.

A mesmerizing true-crime psychological thriller.... The final outcome is a shock. Mr. Finkel tells an enthralling story. From start to finish, this book is hard to put down.

The Art Thief, like its title character, has confidence, élan, and a great sense of timing ... what makes Finkel’s book so much fun is that, without exception, [Breitwieser’s] strategies are insane.

Fascinating… has the pacing and atmosphere of a good suspense tale.

A fascinating read. Finkel will have art history and true crime lovers obsessively turning the pages of this suspenseful, smartly written work until its shocking conclusion.

Masterful ... a riveting ride.

The Art Thief chronicles one of the most outrageous crime sprees in history: In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Stéphane Breitwieser stole from more than 200 museums and galleries across Europe, amassing a collection worth an estimated $2 billion. He never resorted to violence – his audacious thefts all occurred during daylight hours, most with the aid of his girlfriend, Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus, who served as lookout. And unlike nearly every other art thief, Breitwieser did not steal for money. He displayed his treasures in a secret lair where he and his girlfriend could admire them. Yet even more astounding than his crimes is the spectacular events that brought everything crashing down. The Art Thief, based on a series of exclusive interviews with Breitwieser, the first he has ever granted to an American journalist, details a riveting story of love, crime, and an insatiable hunger to possess beauty at any cost.

Gallery Of Images

Sleeping Shepherd by François Boucher, c. 1750, oil on wood. Stolen from the Museum of Fine Arts in Chartres, France. (Credit: © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, N.Y.)

Sibylle of Cleves by Lucas Cranach the Younger, c. 1540, oil on wood. Stolen from New Castle in Baden-Baden, Germany. (Credit: open-source usage.)

Tobacco box painted by Jean-Baptiste Isabey, c. 1805, gold, enamel, and ivory. Stolen from the Valais History Museum in Sion, Switzerland. (Credit: Valais History Museum, MV 1444. © Musées cantonaux du Valais, Sion. Photograph by Heinz Preisig, photo-colorization by Dana Keller.)

Madeleine de France by Corneille de Lyon, 1536, oil on wood. Stolen from the Museum of Fine Arts in Blois, France. (Credit: © Bridgeman Images.)

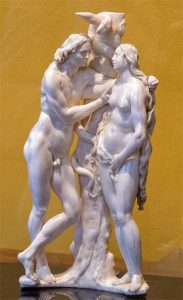

Adam and Eve by Georg Petel, 1627, ivory. Stolen from the Rubens House in Antwerp, Belgium. (Credit: RH.K.015, Collection of the City of Antwerp, Rubens House.)

The Apothecary by Willem van Mieris, c. 1720, oil on wood. Stolen from the Pharmacy Museum in Basel, Switzerland. (Credit: © Pharmaziemuseum Universität Basel, Schweiz.)

Chalice, c. 1590, silver and nautilus shell. Stolen from the Art & History Museum in Brussels, Belgium. (Credit: © Royal Museums of Art & History, Brussels.)

Three Graces by Gérard van Opstal, c. 1650, ivory. Stolen from the Art & History Museum in Brussels, Belgium. (Credit: © Royal Museums of Art & History, Brussels.)

Commemorative medallion, c. 1845, gold-plated silver. Stolen from the History Museum in Lucerne, Switzerland. (Credit: Courtesy of the Art and History Museum of Fribourg.)

Warship, c. 1700, silver. Stolen from the Art & History Museum in Brussels, Belgium. (Credit: ImageStudio / © Royal Museums of Art & History, Brussels.)

Chalice by I.D. Clootwijck, 1588, silver and coconut. Stolen from the Art & History Museum in Brussels, Belgium. (Credit: ImageStudio / © Royal Museums of Art & History, Brussels.)

Chalice, 1602, silver and ostrich egg. Stolen from the Art & History Museum in Brussels, Belgium. (Credit: ImageStudio / © Royal Museums of Art & History, Brussels.)

Landscape with a Cannon by Albrecht Dürer, 1518, paper engraving. Stolen from the Fine Arts Museum in Thun, Switzerland. (Credit: Fletcher Fund, 1919 / The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Scene from the life of Christ, c. 1620, Lindenwood. Stolen from the Art and History Museum in Fribourg, Switzerland. (Credit: Courtesy of the Art and History Museum of Fribourg.)

Festival of Monkeys by David Teniers the Younger, c. 1630, oil on copper. Stolen from the Thomas Henry Museum in Cherbourg-en-Cotentin, France. (Credit: © Musée Thomas Henry)

Flintlock pistol by Barth à Colmar, c. 1720, walnut with silver inlay. Stolen from the Museum of the Friends of Thann in Thann, France. (Credit: Courtesy of La Société d’histoire, “Les Amis de Thann.”)

Still life by Jan van Kessel the Elder, 1676, oil on copper. Stolen from the European Fine Art Foundation in Maastricht, Netherlands. (Credit: © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images.)

Breitwieser’s mother’s house in Alsace, France. The top two windows look into the attic rooms that contained an estimated $2 billion in stolen art. (Credit: Michael Finkel)

A drawing Breitwieser made for the police, with specific dimensions and details, from memory. (Credit: Jean-Claude Morisod)

The Alsacian village of Thann, where Stéphane Breitwieser and Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus committed their first theft together, of an 18th century flintlock pistol. (Credit: Michael Finkel)

The Alsace region of France, where Breitwieser grew up, sits in the northeastern corner of the country, along the borders of Germany and Switzerland. (Credit: Christophe Dumoulin / Getty Images)

In a partially-drained section of the Rhone-Rhine Canal in eastern France, crews search for stolen artwork that had been tossed into the murky water. (Credit: Cedric Joubert / AP)

Breitwieser, in his usual disguise, fake glasses and a baseball cap, stares at the ivory Adam and Eve he’d previously stolen. (Credit: Michael Finkel)

Stéphane Breitwieser (center) and his attorney, Jean-Claude Morisod (left), entering court in Gruyères, Switzerland in 2003. (Credit: © Luzerner Zeitung)

Sleeping Shepherd by François Boucher, c. 1750, oil on wood. Stolen from the Museum of Fine Arts in Chartres, France. (Credit: © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, N.Y.)

Sibylle of Cleves by Lucas Cranach the Younger, c. 1540, oil on wood. Stolen from New Castle in Baden-Baden, Germany. (Credit: open-source usage.)

Tobacco box painted by Jean-Baptiste Isabey, c. 1805, gold, enamel, and ivory. Stolen from the Valais History Museum in Sion, Switzerland. (Credit: Valais History Museum, MV 1444. © Musées cantonaux du Valais, Sion. Photograph by Heinz Preisig, photo-colorization by Dana Keller.)

Madeleine de France by Corneille de Lyon, 1536, oil on wood. Stolen from the Museum of Fine Arts in Blois, France. (Credit: © Bridgeman Images.)

Adam and Eve by Georg Petel, 1627, ivory. Stolen from the Rubens House in Antwerp, Belgium. (Credit: RH.K.015, Collection of the City of Antwerp, Rubens House.)

The Apothecary by Willem van Mieris, c. 1720, oil on wood. Stolen from the Pharmacy Museum in Basel, Switzerland. (Credit: © Pharmaziemuseum Universität Basel, Schweiz.)

Chalice, c. 1590, silver and nautilus shell. Stolen from the Art & History Museum in Brussels, Belgium. (Credit: © Royal Museums of Art & History, Brussels.)

Three Graces by Gérard van Opstal, c. 1650, ivory. Stolen from the Art & History Museum in Brussels, Belgium. (Credit: © Royal Museums of Art & History, Brussels.)

Commemorative medallion, c. 1845, gold-plated silver. Stolen from the History Museum in Lucerne, Switzerland. (Credit: Courtesy of the Art and History Museum of Fribourg.)

Warship, c. 1700, silver. Stolen from the Art & History Museum in Brussels, Belgium. (Credit: ImageStudio / © Royal Museums of Art & History, Brussels.)