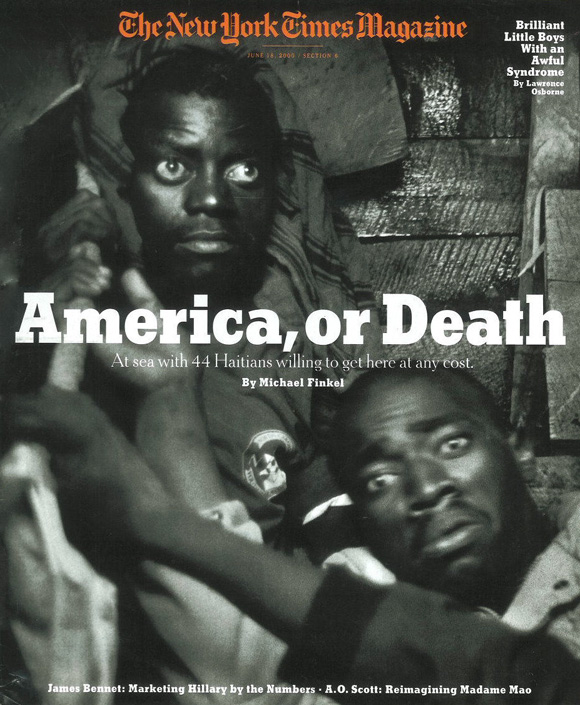

Down in the hold, beneath the deck boards, where we were denied most of the sun’s light but none of its fire, it sometimes seemed as if there were nothing but eyes. The boat was twenty-three feet long, powered solely by two small sails. There were forty-one people below and five above. All but myself and my travel partner were Haitian citizens fleeing their country, hoping to start a new life in the United States. The hold was lined with scrap wood and framed with hand-hewn joists, as in an old mine tunnel, and when I looked into the darkness it was impossible to tell where one person ended and another began. We were compressed together, limbs entangled, heads upon laps, a mass so dense there was scarcely room for motion. Conversation had all but ceased. If not for the shifting and blinking of eyes there’d be little sign that anyone was alive.

Twenty hours before, the faces of the people around me seemed bright with the prospect of reaching a new country. Now, as the arduousness of the crossing became clear, their stares conveyed the flat helplessness of fear. David, whose journey I had followed from his hometown of Port-au-Prince, buried his head in his hands. He hadn’t moved for hours. “I’m thinking of someplace else,” is all he would reveal.

Stephen, who had helped round up the passengers, looked anxiously out the hold’s square opening, four feet over our heads, where he could see a corner of the sail and a strip of cloudless sky. “I can’t swim,” he admitted softly. Kenton, a thirteen-year-old boy, sat in a puddle of vomit and trembled as though crying, only there were no tears. I was concerned about the severity of Kenton’s dehydration and could not shake the thought that he wasn’t going to make it.

“Some people get to America, and some people die,” David had said. “Me, I’ll take either one. I’m just not taking Haiti anymore.”

—

It had been six weeks since David had made that pronouncement. This was in mid-March of 2000, in Port-au-Prince, soon after Haiti’s national elections had been postponed for the fifth time and the country was entering its second year without a parliament or regional officials. David sold mahogany carvings on a street corner not far from the United States Embassy. He spoke beautiful English, spiced with pitch-perfect sarcasm. His name wasn’t really David, he said, but it’s what people called him. He offered no surname. He said he’d once lived in America but had been deported. He informed me, matter-of-factly, that he was selling souvenirs in order to raise funds to pay a boat owner to take him back.

David was not alone in his desire to leave Haiti. About eighty percent of Haiti’s population lives in poverty, and fewer than one in twenty Haitians has a steady wage-earning job. Per capita income is less than $400. There’s rampant violence in the cities and a palpable feeling of despair. Just before I visited, the State Department released the results of a survey conducted in nine Haitian cities. Based on the study, two-thirds of Haitians — nearly five million people — “would leave Haiti if given the means and opportunity.” If they were going to leave, though, most would have to do so illegally; each year, the United States issues about 10,000 immigration visas to Haitian citizens, satisfying about one-fifth of one percent of the estimated demand.

To illegally enter America, Haitians typically embark on a two-step journey, taking a boat first to the Bahamas and then later to Florida. Most are on marginally seaworthy vessels; every Haitian seems to know a dozen stories about sinking boats and passengers left to drift until they are claimed by exhaustion or dehydration or sharks. Such stories did not deter David. He said he was committed to making the trip, no matter the risks. His frankness was unusual. Around foreigners, most Haitians are reserved and secretive. David was boastful and loud. It’s been said that Creole, the lingua franca of Haiti, is ten percent grammar and ninety percent attitude, and David exercised this ratio to utmost effectiveness.

It also helped that he was big, well over six feet and bricked with muscle. His head was shaved bald; a sliver of mustache shaded his upper lip. He was twenty-five years old. He used his size and his personality as a form of self-defense: The slums of Port-au-Prince are as dangerous as any in the world, and David, who had once been homeless for more than a year, had acquired the sort of street credentials that lent his words more weight than those of a policeman or soldier. He lived in a broken-down neighborhood called Projet Droullard, where he shared a one-room hovel with thirteen others — the one mattress was suspended on cinder blocks so that people could sleep not only on but also beneath it. David was a natural leader, fluent in English, French, and Creole. His walk was the chest-forward type of a boxer entering the ring. Despite his apparent candor, it was difficult to know what was really on his mind. Even his smile was ambiguous — the broader he grinned the less happy he appeared.

—

The high season for illegal immigration is April through September. The seas this time of year tend to be calm, except for the occasional hurricane. I mentioned to David that I, along with my travel partner, a photographer named Chris Anderson, wanted to document a voyage from Haiti to America. I told David that if he was ready to make the trip, I’d pay him $30 a day to aid as guide and translator. He was skeptical at first, suspicious that we were working undercover for the C.I.A. to apprehend smugglers. But after repeated assurances, and after showing him the supplies we’d brought for the voyage — self-inflating life vests (including one for David), vinyl rain jackets, waterproof flashlights, Power Bars, and a first-aid kit — his wariness diminished. I offered him an advance payment of one day’s salary.

“Okay,” he said. “It’s a deal.” He promised he’d be ready to leave early the next morning.

David was at our hotel at 5:30 a.m., wearing blue jeans, sandals, and a T-shirt, and carrying a black plastic bag. Inside the bag was a second T-shirt, a pair of socks, a tin bowl, a metal spoon, and a Bible. In his pocket was a small bundle of money. This was all he took with him. Later, he bought a toothbrush.

David opened his Bible and read Psalm Twenty-Three aloud: Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, and then we walked to the bus station, sidestepping the stray dogs. We boarded an old school bus, thirty-six seats, seventy-two passengers, and headed north, along the coast, to Île de la Tortue — Turtle Island — one of the three major boat-building centers in Haiti. David knew the island well. A year earlier, he’d spent a month there trying to gain a berth on a boat. Like many Haitians who can’t afford such a trip, he volunteered to work. Seven days a week, he hiked deep into the island’s interior, where a few swatches of forest still remained, and hacked down pine trees with a machete, hauling them back to be cut and hammered into a ship. For his efforts, David was served one meal a day, a bowlful of rice and beans. After thirty days of labor there was still no sign he’d be allowed onto a boat, so he returned to his mahogany stand in Port-au-Prince.

The bus rattled over the washboard roads and the sun bore down hard, even at seven in the morning. A roadside billboard, faded and peeling, advertised Carnival Cruise Lines. “Les Belles Croisières,” read the slogan — The Beautiful Cruises. At noon, we transferred to the bed of a pickup truck, the passing land gradually surrendering fertility until everything was brown. Five hours later the road ended at the rough-edged shipping town of Port-de-Paix, where we boarded a dilapidated ferry and set off on the hour-long crossing to Île Tortue, a fin-shaped wisp of land twenty miles long and four miles wide. Here, said David, is where he’d begin his trip to America.

There are at least seven villages on Île Tortue — its population is about 30,000 — but no roads, no telephones, no running water, no electricity, and no police. Transportation is strictly by foot, via a web of thin trails lined with cactus bushes. David walked the trails, up and down the steep seafront bluffs, until he stopped at La Vallée, a collection of huts scattered randomly along the shore. On the beach I counted seventeen boats under construction. They looked like the skeletons of beached whales. Most were less than thirty feet long, capable of holding forty to fifty passengers, but two were of the same cargo-ship girth as the boat that had tried a rare Haiti-to-Florida nonstop in January of 2000, a few months before our trip, but was intercepted by the U.S. Coast Guard off Key Biscayne, Florida. Three hundred ninety-five Haitians, fourteen Dominicans, and two Chinese passengers were shoehorned aboard, all of whom were returned to Haiti. According to survivors’ reports, ten people had suffocated during the crossing, the bodies tossed overboard.

The boats at La Vallée were being assembled entirely with scrap wood and rusty nails; the only tools I saw were hammers and machetes. David said a boat left Île Tortue about once every two or three days during the high season. He thought the same was true at the other two boat-building spots — Cap-Haïtien, in the north, and Gonïaves, in the west. This worked out to about a boat a day, forty or more Haitians leaving every twenty-four hours.

The first step in getting onto a boat at Île Tortue, David said, is to gain the endorsement of one of the local officials, who are often referred to as elders. Such approval, he explained, is required whether you are a foreigner or not — and foreigners occasionally come to Haiti to arrange their passage to America. A meeting with the elder in La Vallée was scheduled. David bought a bottle of five-star rum as an offering, and we walked to his home.

The meeting was tense. David, Chris, and I crouched on miniature wooden stools on the porch of the elder’s house, waiting for him to arrive. About a dozen other people were present, all men. They looked us over sharply and did not speak or smile. When the official appeared, he introduced himself as Mr. Evon. He did not seem especially old for an elder, though perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised; the average life expectancy for men in Haiti is less than fifty years. When Haitian men discuss serious matters, they tend to sit very close to one another and frequently touch each other’s arms. David placed both his hands upon Mr. Evon and attested, in Creole, to the availability of funds for the trip and to our honesty.

“What are your plans?” asked Mr. Evon.

“To go to America,” David said. “To start my life.”

“And if God does not wish it?”

“Then I will go to the bottom of the sea.”

That evening, several of the men who had been present during our interview with Mr. Evon came to visit, one at a time. They were performing what David called a “vit ron” — a quick roundup, trying to gather potential passengers for the boat they were each affiliated with. David chose an amiable man named Stephen Bellot, who claimed to be filling a ship that was likely to leave in a matter of days. Stephen was also a member of one of the more prominent families on Île Tortue. He was twenty-eight years old, lanky and loose-limbed, with rheumy eyes and a wiggly way of walking that made me think, at times, that he’d make an excellent template for a cartoon character.

In many ways, he seemed David’s opposite. Where David practically perspired bravado, Stephen was tentative and polite. His words were often lost in the wind, and he had a nervous habit of rubbing his thumbs across his forefingers, as if they were little violins. He had been raised on Île Tortue and, though he’d moved to Port-au-Prince to study English, he seemed to lack David’s city savviness. In Port-au-Prince, Stephen had worked for several years as a high school teacher — chemistry and English were his specialties. He was paid $35 a month. He’d returned to Île Tortue six months previous in order to catch a boat to America. The prospect of leaving, he admitted, both inspired and intimidated him. “I’ve never been anywhere,” he told me. “Not even across the border to the Dominican Republic.” He said he’d set up a meeting with a boat owner the next day.

The boat owner lived on the mainland, in Port-de-Paix. Stephen’s mother and brother and grandmother and several of his cousins lived in a small house nearby, and Stephen took us there while he went off to find the captain. An open sewer ran on either side of the two-room cinder-block home; insects formed a thrumming cloud about everyone’s head. There was a TV but the electricity wasn’t working. The lines had been down for some time, and nobody knew when they’d be repaired. Sleep was accomplished in shifts — at all times, it seemed, four or five people were in the home’s one bed. The sole decoration was a poster advertising Miami Beach. We waited there for eleven hours. The grandmother, bone thin, sat against a wall and did not move. Another woman scrubbed clothing with a washboard and stone. “Everyone in Haiti has been to prison,” David once said, “because Haiti is a prison.”

The captain arrived at sunset. His name was Gilbert Marko; he was thirty-one years old. He was wearing the nicest clothing I’d seen in Haiti — genuine Wrangler blue jeans, a gingham button-down shirt, and shiny wingtips. He had opaque eyes and an uncommonly round head, and tiny, high-set ears. There was a sweaty intensity about him, like a person who has recently eaten a habanero pepper. The meeting went well. David explained that his decision to leave had not been a hasty one — he mentioned his previous trip to Île Tortue and his time in America. Stephen said we all understood the risks. Both David and Stephen declared their support for us. This seemed good enough for Gilbert. He said he’d been to the Bahamas many times; before becoming a captain, he had worked as a deckhand. He had seven children by five women and was gradually trying to get everyone to America. He spoke excellent English, jingly with Bahamian rhythms.

His boat, he said, was new — this would only be its second crossing. There would be plenty of water and food, he insisted, and no more than twenty-five passengers. He was taking family members and wanted a safe, hassle-free trip. His boat was heading to Nassau, the Bahamian capital. The crossing could take four days if the wind was good, and as many as eight days if it was not. We’d have no engine.

Most people who make it to America, Gilbert explained, do so only after working in the Bahamas for several months, usually picking crops or cleaning hotel rooms. According to Gilbert, the final segment of the trip, typically a ninety-minute shot by powerboat from the Bimini Islands, Bahamas, to Broward Beach, Florida, costs about $3,000 a person. Often, he said, an American boat owner pilots this leg — ten people in his craft, a nice profit for a half-day’s work.

Eventually, talk came around to money for Gilbert’s segment of the trip. Nothing in Haiti has a set price, and the fee for a crossing is especially variable, often depending on the quality of the boat. Virtually every Haitian is handing over his life savings. The price most frequently quoted for an illegal trip to the Bahamas was 10,000 gourdes — about $530. Fees ten times as high had also been mentioned. Rumor on Île Tortue was that the two Chinese passengers on the Key Biscayne boat had paid $20,000 apiece. Gilbert said that a significant percentage of his income goes directly to the local elders, who in turn make sure that no other Haitian authorities become overly concerned with the business on Île Tortue.

After several hours of negotiations, Gilbert agreed to transport Chris and me for $1,200 each, and David and Stephen, who were each given credit for rounding us up, for $300 each.

—

Gilbert had named his boat Believe in God. It was anchored (next to the Thank You Jesus) off the shore of La Vallée, where it had been built. If you were to ask a second grader to draw a boat, the result would probably look a lot like the Believe in God. It was painted a sort of brackish white, with red and black detailing. The mast was a thin pine, no doubt dragged out of the hills of Île Tortue. There was no safety gear, no maps, no life rafts, no tool kit, and no nautical instruments of any type save for an ancient compass. The deck boards were misaligned. With the exception of the hold, there was no shelter from the elements. Not a single thought had been given to comfort. It had taken three weeks to build, said Gilbert, and had cost $4,000. It was his first boat.

Gilbert explained that he needed to return to Port-de-Paix to purchase supplies, but that it’d be best if we remained on the boat. The rest of his passengers, he said, were waiting in safe houses. “We’ll be set to go in three or four hours,” he said as he and his crew boarded a return ferry.

Time in Haiti is an extraordinarily flexible concept, so when eight hours passed and there was no sign of our crew, we were not concerned. Night came, and still no word. Soon, twenty-four hours had passed since Gilbert’s departure. Then thirty. David became convinced that we had been set up. We’d handed over all our money and everyone had disappeared. Boat-smuggling cons were nothing new. The most common one, David said, involved sailing around Haiti and the Dominican Republic two or three times and then dropping everyone off on a deserted Haitian island and telling them they’re in the Bahamas. A more insidious scam, he mentioned, involved taking passengers a mile out to sea and then tossing them overboard. It happens, he insisted. But this, said David, was a new one. He was furious, but for a funny reason. “They stole all that money,” he said, “and I’m not even getting any.”

—

David was wrong. After dark, Gilbert and his crew docked a ferry alongside the Believe in God. They had picked up about thirty other Haitians — mostly young, mostly male — from the safe houses, and the passengers huddled together as if in a herd, each clutching a small bag of personal belongings. Their faces registered a mix of worry and confusion and excitement; the mind-jumble of a life-altering moment. Things had been terribly delayed, Gilbert said, though he offered no further details. I saw our supplies for the trip: a hundred-pound bag of flour, two fifty-five-gallon water drums, four bunches of plantains, a sack of charcoal, and a rooster in a cardboard box. This did not seem nearly enough for what could be a weeklong trip, but at least it was something. I’d been told that many boats leave without any food at all.

The passengers transferred from the ferry to the Believe in God, and Gilbert sent everyone but his four-man crew down to the hold. We pushed against one another, trying to establish small plots of territory. David’s size in such a situation was suddenly a disadvantage — he had difficulty contorting himself to fit the parameters of the hold and had to squat with his knees tucked up against his chest, a little-boy position. For the first time since I’d met him he appeared weak, and more than a bit tense. Throughout our long wait, David had been a study in nonchalance. “I’m not nervous; I’m not excited; I’m just ready to leave,” he’d said the previous day. Perhaps now, as the gravity of the situation dawned on him, he realized what he was about to undergo.

“Wasn’t it like this last time you crossed?” I asked. David flashed me an unfamiliar look and touched my arm and said, “I need to tell you something,” and finally, in the strange confessional that is the hold of a boat, he told me a little of his past. The first time he’d gone to America, he said, he’d flown on an airplane. He was nine years old. His mother had been granted an immigration visa, and she took David and his two brothers and a sister to Naples, Florida. Soon after, his mother died of AIDS. He had never known his father. He fell into bad company, and at age seventeen spent nine months in jail for stealing a car. At nineteen, he served a year and five days in jail for selling marijuana and then was deported.

In Naples, he said, his friends had called him Six-Four, a moniker bestowed because of his penchant for stealing 1964 Chevy Impalas. He admitted to me that if he returned to Naples, where his sister lived, he was concerned he’d have to become Six-Four again in order to afford to live there. In America, he mentioned, there is shame in poverty — a shame you don’t feel in Haiti. “People are always looking at the poor Haitians who just stepped off their banana boat,” he said. This was an attitude, he suggested, that Stephen might find painful to encounter.

The view from the hold, through the square opening of the scuttle, was like watching a play from the orchestra pit. Gilbert handed each crew member an envelope stuffed with money, as if at a wedding. Nobody was satisfied, of course, and an argument ensued that lasted into the dawn. In the hold, where everyone was crushed together, frustration mounted. Occasionally curses were yelled up. When it was clear there was no more money to distribute, the crew demanded spots on the boat for family members. Gilbert acquiesced, and the crew left the ship to inform their relatives. Soon there were thirty-five people on board, then forty.

Hours passed. There was no room in the hold to do anything but sit, and so that is what we did. People calmed down. Waiting consumes a significant portion of life in Haiti, and this was merely another delay. The sun rode its arc; heat escaping through the scuttle blurred the sky. A container of water was passed about, but only a few mouthfuls were available for each person. Forty-two people were aboard. Then forty-six. It was difficult to breathe, as though the air had turned to gauze. David and Stephen could not have been pressed closer to each other if they’d been wrestling. There had been murders on these journeys, according to David, as well as suicides and suffocations. Now I could see why. “We came to this country on slave boats,” David said, “and we’re going to leave on slave boats.”

There was a sudden pounding of feet on the deck and a man — an old man, with veiny legs and missing teeth — dropped headfirst into the hold. Gilbert jumped after him, seized the old man by his hair and flung him out. I heard the hollow sounds of blows being landed, and then a splash, and the attempted stowaway was gone.

Everything was quiet for a moment, a settling, and then there was again commotion on deck, but it was choreographed commotion, and the sails were raised, a mainsail and a bed-sheet-size jib, two wedges of white against the cobalt sky. We’d already been in the hold ten hours but still the boat did not leave. There was a clipped squawk from above, and the rooster was slaughtered. Then Gilbert came down to our quarters — he’d tied a fuchsia bandanna about his head — and crawled to the very front, where there was a tiny door with a padlock. He stuck his head inside the cubby and hung a few flags, sprayed perfumed water, and chanted. “Voodoo prayers,” said David. When he emerged he crawled through the hold and methodically sprinkled the top of everyone’s head with the perfume. Then he climbed onto the deck and barked a command, and the Believe in God set sail.

—

The poorest country and the richest country in the Western Hemisphere are separated by 600 miles of open ocean. It’s a treacherous expanse of water. The positioning of the Caribbean Islands relative to the Gulf Stream creates what is known as a Venturi effect — a funneling action that can result in a rapid buildup of wind and waves. Meteorologists often call the region “hurricane alley.” For a boat without nautical charts, the area is a minefield of shallows and sandbars and reefs. It is not uncommon for inexperienced sailors to become sucked into the Gulf Stream and fail to reach their destination. “If you miss South Florida,” said Commander Christopher Carter of the Coast Guard, who had sixteen years’ experience patrolling the Caribbean, “your next stop is North Carolina. Then Nova Scotia. We’ve never found any migrants alive in Nova Scotia, but we’ve had ships wash ashore there.”

Initially, the waves out past the tip of Île Tortue were modest, four or five feet at most, the whitecaps no more than a froth of curlicues. Still, the sensation in the hold was of tumbling unsteadiness. The hold was below the waterline, and the sloshing of the surf was both amplified and distorted — the sounds of digestion, it occurred to me, and I thought more than once of Jonah, trapped in the belly of a whale. When the boat was sideswiped by an especially aggressive wave, the stress against the hull invariably produced a noise like someone stepping on a plastic cup. Water came in through the cracks. Every time this happened, David and Stephen glanced at one another and arched their eyebrows, as if to ask, Is this the one that’s going to put us under?

When building a boat, David had said, it was common to steal nails from other ships, hammer them straight and reuse them. I wondered how many nails had been pulled from our boat. As the waves broke upon us, the hull boards bellied and bowed, straining against the pressure. There was a pump aboard, a primitive one, consisting of a rubber-wrapped broom handle and a plastic pipe that ran down to the bottom of the hold. Someone on deck continuously had to work the broom handle up and down, and still we were sitting in water. The energy of the ocean against the precariousness of our boat seemed a cruel mismatch.

Nearly everyone in the hold kept their bags with them at all times; clearly, a few of the possessions were meant to foster good luck. One man repeatedly furled and unfurled a little blue flag upon which was drawn a vévé — a symbolic design intended to invoke a voodoo spirit. Stephen fingered a necklace, carved from a bit of coconut, that a relative had brought him from the Bahamas. David often held his Bible to his chest. I had my own charm. It was a device called an Emergency Position-Indicating Radio Beacon, or EPIRB. When triggered, an EPIRB transmits a distress signal to the Coast Guard via satellite, indicating its exact position in the water. I was assured by the company that manufactured the beacon that if I activated it anywhere in the Caribbean, help would be no more than six hours away. The EPIRB was a foot tall, vaguely cylindrical, and neon yellow. I kept it stashed in my backpack, which I clasped always in my lap. Nobody except Chris, my travel partner, knew it was there.

The heat in the hold seemed to transcend temperature. It had become an object, a weight — something solid and heavy, settling upon us like a dentist’s X-ray vest. There was no way to shove it aside. Air did not circulate, wind was shut out. Thirst was a constant dilemma. At times, the desire to drink crowded out all other notions. Even as Gilbert was sending around a water container, my first thought was when we’d have another. We had 110 gallons of water on board, and forty-six people. In desert conditions, it’s recommended that a person drink about one gallon per day. It was as hot as any desert down there. Hotter. That meant we had a two-day supply. But we were merely sitting, so perhaps half a gallon would be enough. That’s four days. The trip, though, could take eight days. If it did we’d be in serious trouble.

Finding a comfortable position in the hold was hopeless. The hull was V-shaped, and large waves sent everyone sliding into the center, tossing us about like laundry. I exchanged hellos with the people around me — Wesley and Tijuan and Wedell and Andien — but there seemed nothing further to say. Every hour, an electronic watch chirped from somewhere in the dark. One man read from a scrap of a paperback book, Chapters twenty-nine through thirty-three of a work called “Garden of Lies.” From here and there came the murmurs of sleep. The occasional, taut conversations between Stephen and David consisted primarily of reveries about reaching America. David said that he wanted to work in the fields, picking tomatoes or watermelon. His dream was to marry an American woman. Stephen’s fantasy was to own a pickup truck, a red one.

The rules of the boat had been established by Gilbert. Seven people were allowed on deck at once; the rest had to remain in the hold. Five spots were reserved by Gilbert and the crew. The other two were filled on a rotating basis — a pair from the deck switched with a pair from the hold every twenty minutes or so. This meant each person would be allowed out about once every six hours. A crowded deck, Gilbert explained, would interfere with the crew and rouse the suspicions of passing boats. More important, people were needed in the hold to provide ballast — too much weight up top and the boat would tip.

Of the forty-six people on the boat, five were women. They were crammed together into the nether reaches of the hold, visible only as silhouettes. The further back you crawled into the hold, the hotter it got. Where the women were it must have been crippling. Occasionally they braided one another’s hair, but they rarely seemed to speak. They were the last to be offered time on deck, and their shifts seemed significantly shorter than those of the men.

The oldest person on the boat was a forty-year-old passenger named Desimeme; the youngest was thirteen-year-old Kenton. The average age was about twenty-five. Unlike the migrants of the early 1990s, who tended more heavily to be families and rural peasants, most Haitian escapees were now young, urban males. The reason for this shift was probably an economic one. According to people on Île Tortue, the price for a crossing had recently become vastly inflated, and women and farmers are two of Haiti’s lowest-paid groups.

Two hours after leaving, the seasickness began. There was a commotion in the rear of the hold, and people started shouting, and a plastic yellow container — at one time it was a margarine tub — was tossed below. It was passed back. The man who was sick had filled it up, and the container was sent forward, handed up, dumped overboard, and passed back down. A dozen pairs of hands reached for it. The yellow container went back and forth. It also served as our bathroom, an unavoidable humiliation we each had to endure. Not everyone could wait for the container to arrive, and in transferring the margarine tub in pitching seas it was sometimes upended. The contents mingled with the water that sloshed ankle-deep about the bottom of the hold. The stench was overpowering.

One of the sickest people on board was Kenton, the thirteen-year-old boy. He lay jackknifed next to me in the hold, clutching his stomach, too ill to grab for the bucket. I slipped him a seasickness pill, but he was unable to keep it down. Kenton was a cousin of one of the crew members. He had been one of the last people to board the boat. In the scramble to fill the final spots, there was no room for both him and his parents, so he was sent on alone. His parents, I’d overheard, had promised that they’d be on the very next boat, and when Kenton boarded he was bubbly and smiling, as if this were going to be a grand adventure. Now he was obviously petrified, but also infused with an especially salient dose of Haitian mettle — as he grew weaker he kept about him an iron face. Never once did he cry out. He had clearly selected a favorite shirt for the voyage: a New York Knicks basketball jersey.

This did not seem like the appropriate time to eat, but dinner was ready. The boat’s stove, on deck, was an old automobile tire rim filled with charcoal. There was also a large aluminum pot and a ladle. The meal consisted of dumplings and broth — actually, boiled flour balls and hot water. Most people had brought a bowl and spoon with them, and the servings were passed about in the same manner as the margarine container. When the dumplings were finished, Hanson, one of the crew members, came down into the hold. He was grasping a plastic bag that was one of his personal possessions. Inside the bag was an Île Tortue specialty — ground peanuts and sugar. He produced a spoon from his pocket, dipped it into the bag, and fed a spoonful to the man nearest him, carefully cupping his chin as if administering medicine. Then he wormed his way through the hold, inserting a heaping spoon into everyone’s mouth. His generosity was appreciated, but the meal did little to help settle people’s stomachs. The yellow container was again in great demand.

Hours trickled by. There was nothing to do, no form of diversion. The boat swayed, the sun shone, the heat intensified. People were sick; people were quiet. Eyes gradually dimmed. Everyone seemed to have withdrawn into themselves, as in the first stages of shock. Heads bobbed and hung, fists clenched and opened. Thirst was like a tight collar about our throats. It was the noiselessness of the suffering that made it truly frightening — the silent panic of deep fear.

Shortly before sunset, when we’d been at sea nearly twelve hours, I was allowed to take my second stint on deck. By now there was nothing around us but water. The western sky was going red and our shadows were at full stretch. The sail snapped and strained against its rigging, but the waves didn’t seem to be knocking us about as much. Gilbert was standing at the prow, gazing at the horizon, a hand cupped above his eyes, and as I watched him a look of concern came across his face. He spun around, distressed, and shouted one word: “Hamilton!” Everyone on deck froze. He shouted it again. Then he pointed to where he’d been staring, and there, in the distance, was a ship of military styling, marring the smooth seam between sea and sky. Immediately, I was herded back into the hold.

A Hamilton, Stephen whispered, is Haitian slang for a Coast Guard ship — it’s also, not coincidentally, the name of an actual ship. The news flashed through the hold, and in reflexive response everyone crushed deeper into the rear, away from the opening, as though this would help avoid detection. Gilbert paced the deck, manic. He sent two of the crew members down with us, and then he, too, descended. He burrowed toward his cubby, shoving people aside, unlocked the door, and wedged himself in. And then he began to chant, in a steady tone both dirgelike and defiant. The song paid homage to Agwe, the Voodoo spirit of the sea, and when Gilbert emerged, still chanting, several people in the hold took up the tune, and then he climbed up on deck and the crew began chanting, too. It was an ethereal tune, sung wholly without joy, a signal of desperate unity that seemed to imply we’d sooner drift to Nova Scotia than abandon our mission. Some on the boat, it seemed, really were willing to sacrifice their lives to try and get to America. Our captain was one of them.

Over the singing came another sound, an odd buzz. Then there were unfamiliar voices — non-Haitian voices, speaking French. In the hold, everyone woke from their stupor. Stephen grabbed his necklace. David chewed on the meat of his palm. I stood up and peeked out. The buzz was coming from a motorized raft that had pulled beside us. Six people were aboard, wearing orange life vests imprinted with the words u.s. coast guard. Gilbert was sitting atop one of our water drums, arms folded, flashing our interlopers a withering look. Words were shouted back and forth — questions from the Coast Guard, blunt rejoinders from Gilbert.

“Where are you headed?”

“Miami.”

“Do you have docking papers?”

“No.”

“What are you transporting?”

“Rice.”

“Can we have permission to board?”

“No.”

There was nothing further. In the hold everyone was motionless. People tried not to breathe. Some had their palms pushed together in prayer. One man pressed his fingertips to his forehead. Soon I heard the buzz again, this time receding, and the Coast Guard was gone. Gilbert crouched beside the scuttle and spoke. This had happened on his last crossing, he said. The Coast Guard just comes and sniffs around. They were looking for drugs, but now they’ve gone. Then he mentioned one additional item. As a precaution, he said, nobody would be allowed onto the deck, indefinitely.

The reaction to this news was subtle but profound. There was a general exhalation, as if we’d each been kicked in the stomach, and then a brief burst of conversation — more talking than at any time since we’d set sail. The thought of those precious minutes on deck had been the chief incentive for enduring the long hours below. With Gilbert’s announcement, something inside of me — some scaffolding of fortitude — broke. We’d been at sea maybe fourteen hours; we had a hundred to go, minimum. Ideas swirled about my head, expanding and consuming like wildfire. I thought of drowning, I thought of starving, I thought of withering from thirst.

Then, as if he’d read my mind, David took my right hand and held it. He held it a long time, and I felt calmer. He looked at my eyes; I looked at his. This much was clear: David wasn’t willing to heed his own words. He wasn’t prepared to die. He was terrified, too. This wasn’t something we discussed until much later, though he eventually admitted it.

When David let go of my hand, the swirling thoughts returned. I wrestled with the idea of triggering the EPIRB. People were weak — I was weak — and it occurred to me that I had the means to save lives. But though pressing the button might lead to our rescue, it would certainly dash everyone’s dreams. There was also the concern that I’d be caught setting it off, the repercussions of which I did not want to ponder. I made a decision.

“Chris,” I said. I was whispering.

“Yes.”

“I’m going to use the thing.”

“Don’t.”

“Don’t?”

“No, don’t. Wait.”

“How long?”

“Just wait.”

“I don’t think I can.”

“Just wait a little.”

“Okay. I’ll wait a little.”

—

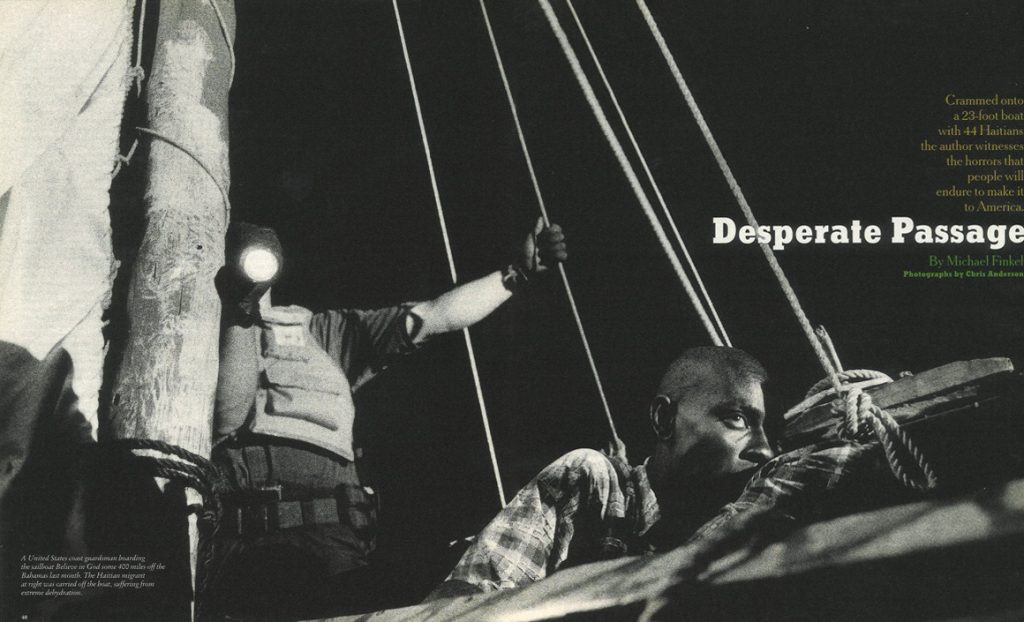

I waited a little, a minute at a time. Four more hours passed. Then, abruptly, the buzz returned. Two buzzes. This time there was no conversation, only the clatter of Coast Guard boots landing on our deck. At first, it seemed as though there might be violence. The mood in the hold was one of reckless, nothing-to-lose defiance. I could see it in the set of people’s jaws, and in the vigor that suddenly leapt back into their eyes. This was our boat; strangers were not invited — they were to be pummeled and tossed overboard, like the old man who had tried to stow away. Then lights were shined into the hold, strong ones. We were blinded. There was no place for us to move. The idea of revolt died as quickly as it had ignited. Eighteen hours after we’d set sail, the trip was over.

Six at a time, we were loaded into rubber boats and transported to the Coast Guard cutter Forward, a ship 270 feet long and nine stories high. It was four o’clock in the morning. Nobody struggled, no weapons were drawn. We were frisked and placed in quarantine on the flight deck, in a helicopter hangar. Three Haitians were so weak from dehydration that they needed assistance walking. The Coast Guard officers were surprised to see journalists on board, but we were processed with the other Haitians. We were each supplied with a blanket, a pair of flip-flops, and a toothbrush. We were given as much water as we could drink. We were examined by a doctor. Crew members on the Forward wore two layers of latex gloves whenever they were around us.

The Forward’s commanding officer, who’d served in the Coast Guard for nineteen years, was named Dan MacLeod. He came onto the flight deck and pulled me aside. The Coast Guard, he said, had not lost sight of our boat since we’d first been spotted. He’d spent the previous four hours contacting Haitian authorities, working to secure an S.N.O. — a Statement of No Objection — that would permit the Coast Guard to stop a Haitian boat in international waters. When David and Stephen learned of this, they were furious. There is the feeling among many Haitians of abandonment by the United States — or worse, of manipulation. Because there is democracy in Haiti, the United States has a simple excuse for rejecting Haitian citizenship claims: Haitians are economic, not political migrants. For those Haitians who do enter America illegally — the United States Border Patrol estimates that between 6,000 and 12,000 do so each year — it is far better to try and seep into the fabric of the Haitian-American community than to apply for asylum. Some years, more than ninety percent of Haitian asylum claims are rejected.

As soon as the Haitian government granted permission, the Coast Guard had boarded our boat. Though illegal migrants were suspected to be on board — two large water barrels seemed a bit much for just a crew — the official reason the boat had been intercepted, Officer MacLeod told me, was because we were heading straight for a reef. “You were off course from Haiti about two degrees,” he said. “That’s not bad for seat-of-the-pants sailing, but you were heading directly for the Great Inagua reef. You hadn’t altered your course in three hours, and it was dark out. When we boarded your vessel you were 2,200 yards from the reef. You’d have hit it in less than forty minutes.”

Our boat running against a reef could have been lethal. The hull, likely, would have split. The current washing over the reef, Officer MacLeod informed me, is unswimmably strong. The reef is as sharp as a cheese grater. The EPIRB would not have helped.

Even if we’d managed to avoid the reef — if, by some good fortune, we’d changed course at the last minute — we were still in danger. Officer MacLeod asked me if I’d felt the boat become steadier as the night progressed. I said I had. “That’s the first sure sign you’re sinking,” he said. There was more. “You were in three-to-four-foot seas. At six-foot seas, you’d have been in a serious situation, and six-foot seas are not uncommon here. Six-foot seas would’ve taken that boat down.” When I mentioned that we’d expected the trip to take four or five days, Officer MacLeod laughed. “They were selling you a story,” he said. In the eighteen hours since leaving Haiti, we had covered thirty miles. We’d had excellent conditions. The distance from Haiti to Nassau was 450 miles. Even with miraculous wind, it could have taken us ten days. The Coast Guard doctor said we’d most likely have been dealing with fatalities within forty-eight hours.

The next day, it turned out, was almost windless. It was hotter than ever. And the seas were choppy — seven feet at times, one officer reported. Another high-ranking officer added one more bit of information: A Coast Guard ship hadn’t been in these waters at any time in the past two weeks. The Forward happened to be heading in for refueling when we were spotted.

Our trip, it appeared, had all the makings of a suicide mission. If there had been no EPIRB and no Coast Guard, it’s very likely that the Believe in God would have vanished without a trace. And our craft, said Officer MacLeod, was one of the sturdier sailboats he has seen — probably in the top twenty percent. Most boats that make it, he mentioned, have a small motor. I wondered how many Haitians have perished attempting such a crossing. “That’s got to be a very scary statistic,” said Ron Labrec, a Coast Guard public affairs officer, though he wouldn’t hazard a guess. He said it’s impossible to accurately determine how many migrants are leaving Haiti and what percentage of them make it to shore.

But given the extraordinary number of people fleeing on marginal sailboats, it seems very likely that there are several hundred unrecorded deaths each year. Illegal migration has been going on for decades. It is not difficult to imagine that there are thousands of Haitian bodies on the bottom of the Caribbean.

We spent two days on the Forward, circling slowly in the sea, while it was determined where we would be dropped off. Then everyone was deposited on Great Inagua Island and turned over to Bahamian authorities. Chris and I were released and the Haitians were placed in a detention center. The next day they were flown to Nassau and held in another detention center, where they were interviewed by representatives of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees. None were found to qualify for refugee status.

As for the Believe in God, the boat came to a swift end. The night we were captured, we stood along the rail of the flight deck as the Forward’s spotlight was trained on our boat. It looked tiny in the ink-dark sea. The sail was still up, though the boat was listing heavily. Officer MacLeod had just started telling me about its unseaworthiness, and explained that the Coast Guard had cut a few extra holes in it, to accelerate the sinking, so it wouldn’t be a hazard to cargo ships. “Watch,” he said. As I looked, the mast leaned farther and farther down, as if bowing to the sea, until it touched the water. Then the boat slowly disappeared.

—

After two weeks in a detention center, all forty-four Haitians were flown from Nassau to Port-au-Prince. They received no punishment from Haitian authorities. The next morning, Gilbert returned to Île Tortue, already formulating plans for purchasing a second boat and trying to cross once more. Stephen also went home to Île Tortue, but was undecided as to whether he’d try the journey again.

David went back to Port-au-Prince, back to his small mahogany stand, back to his crumbling shack, where his personal space consisted of a single nail from which he hung the same black plastic bag he’d had on the boat. He said he felt lucky to be alive. He said he would not try again by boat, not ever. Instead, he explained, he was planning on sneaking overland into the Dominican Republic. There were plenty of tourists there and he’d be able to sell more mahogany. He told me he was already studying a new language, learning from a Spanish translation of “The Cat in the Hat” that he’d found in the street.

— end —